First Chapter Feature: Simple, Safe & Secret

By Eve Carson A haunting true story of family, silence, and survival.

When Eve Carson’s stepfather was murdered, she uncovered secrets that shattered everything she thought she knew.

This is where the real story begins.

Chapter One—“Oh, Men of Dark and Dismal Fate”

The audience rose to their feet with thunderous applause as the ensemble reached the crescendo at the end of Act I. Joan tapped her gray shoes still humming “Oh, Men of Dark and Dismal Fate.” She loved the theater and the exhilaration of New York City. The empty seat next to her in the heaving playhouse was the only blight on her otherwise perfect evening of Friday, November 27, 1981.

As the curtain rose for the second act of The Pirates of Penzance. Joan settled back into her seat next to her parents and her sister, Anne. Their older brother, Steve, was half a country away, living in Illinois with his pregnant wife, Eve. Joan smiled, not daring to show her disappointment. Family logistics nixed the planned visit of her friend over the Thanksgiving break. The Websters organized their calendars down to the smallest detail. The shift in the schedule was out of character, but the adjustment set the stage for the dramatic chain of events about to unfold.

Joan’s father George nodded to the songs of Gilbert and Sullivan as the actors belted out uncanny premonitions in Act II. The comedic constables on the stage voiced a logical notion. When criminals were not engaged in their enterprise, they did normal things anyone might do. The players’ lyrics warned of impending despair, keeping the audience on the edge of their seats. Joan’s mother Eleanor thumbed the pages of her Playbill. Subliminal messages, delivered in an entertaining performance, reassured her everything was prepared. A swashbuckling troupe challenged the young actor on stage with a paradox when he left the fold. The verses held more meaning than Joan could have foreseen. The librettos projected a dismal fate for the lamb straying from the flock and the contradictions of her guardian.

When the curtain came down on the musical comedy, George, Eleanor, Anne, and Joan walked out of the Minskoff Theatre on W. 45th Street in New York City’s theater district. George played the soundtrack cassette in the car as he drove to a favorite watering hole for a nightcap. Cosmos knew George by name and gladly entertained his requests on the piano. Joan’s father gulped down his Scotch and placed a folded bill in Cosmos’ gratuity snifter. The patriarch subtly signaled to his brood; it was time to leave. Docilely, his entourage took their positions in the blue Buick station wagon. George turned into the Lincoln Tunnel headed for home turf in New Jersey.

The family entered the house through the garage door by the pantry. The girls headed upstairs for the night, and Eleanor settled in the den to watch the late news. George opened the liquor cabinet and poured another two fingers of Scotch. He carried the bottle to the den and placed it on the mirrored table beside him. His body gradually slid to an uncomfortable, half-reclined posture on the loveseat: his head tilted back, bobbing unsupported, and his spectacles askew. The guttural tone of George’s voice resonated as he mumbled and snored in a semi-conscious stupor. The pattern was familiar. Eventually, Eleanor nudged and coaxed her husband to bed.

The girls were already in place at the small kitchen table the next morning. George walked through the front hall and tapped the turtle’s tail announcing his presence. The turtle was a whimsical dinner bell, a symbol of the privilege of George’s upbringing. Eleanor busied herself dutifully in the kitchen. She moved to the table with George’s first course and a hot cup of coffee. As she sashayed through the kitchen, the itinerary tacked on the refrigerator rustled and reminded George to coordinate the day with his fledglings. His upcoming trip was uncharacteristic. As a senior executive with International Telephone & Telegraph (ITT) in Nutley, New Jersey, George would normally delegate rather than interrupt his holiday. The impending agenda demanded his personal attention. None but the person in charge could know the full purpose of his mission.

George went to the cupboard to add some libation to his second course. The Bloody Mary began the daily ritual of numbing his senses. He pushed up his wire-rimmed glasses to peruse the news of the day in the paper. Only an occasional grunt suggested a story caught his attention. He pushed away from the table and headed back upstairs while Eleanor played the scullery maid, clearing the dishes. Dark, sullen eyes stared back at George from the bathroom mirror. He ran his fingers through his thick, wavy mane before splashing on the hair tonic to slick back the curves.

Joan retreated to her room to pack her belongings. She folded the essentials she had brought home for the long weekend and tucked them neatly in her Lark suitcase. She tossed a single green sock in her bag hoping its partner was back at the dorm. She carefully wrapped the folded clothes around a stack of photographs, memories from the family’s summer vacation in Nantucket. When Joan opened her bedroom door, she heard the door across the hall shut tightly. Her bedroom sat across the hallway from George’s upstairs small study. She could hear her father’s low guttural tones talking on his private line as she pulled bed linens out of the closet to take back to school. That second line into the house sat on George’s desk and was off limits. It was the rule of the house not to disturb George in his office.

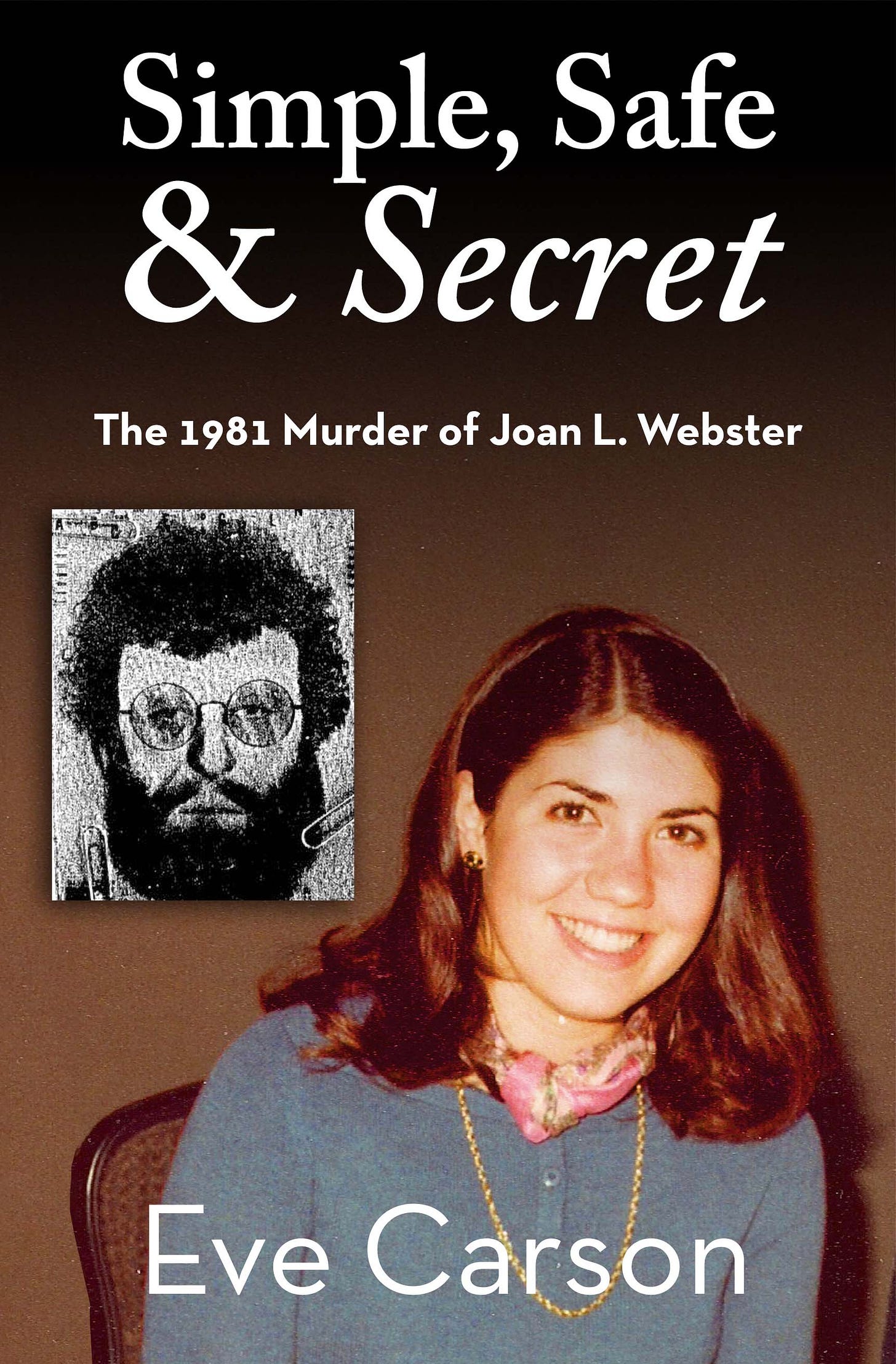

The baby of the family, with two older siblings, Joan was a 25-year-old student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Before returning to school, she lived in Manhattan for two years, working for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. The independent student had even traveled alone through Europe. During her time in New York City, the petite young woman was the victim of a street crime when an assailant snatched her purse. She learned to be aware of her surroundings. As the dorm proctor at Perkins Hall, she passed along safety tips to the coeds she mentored. In her second year of graduate school, she was an excellent, award-winning student with a promising future.

On the Monday before the Thanksgiving break, Joan had presented an 11-week auditorium project to rave reviews before riding to New Jersey with her sister. It was disappointing her friend couldn’t come to visit as planned, but George’s trip over the weekend took precedence for the family. Rather than wait to ride back to Boston with Anne on Sunday, George made arrangements and scheduled a flight for Joan on Saturday night.

Eleanor announced that lunch was ready. George made his way back to the kitchen table, poured a glass of beef broth, and diluted the consommé with a shot of vodka. He confirmed that everyone knew the drill. The foursome would grab an early bite at the club before making the rounds and then drive Joan to Newark Airport. Everything was planned down to the minutest detail as if they had synchronized watches.

Joan collected a few last-minute items and stuck them in her leather carry-on tote bag. She added a few vinyl records from the musicals she enjoyed on Broadway, the Playbill from the night before, rolled up sketches and architectural pamphlets, and her pair of gray shoes.

The upper-middle-class family fit a finely tuned image. In public, the Websters embodied all the social graces to be on every guest list. Their credentials boasted all of the best schools and social connections. The charismatic men in the Webster family were engaging pied pipers. George and his son Steve often played the piano and entertained listeners with humorous tales. Irish wit and charm centered them in any gathering, and they relished the adulation. To the outside observer, they were a perfect family in complete harmony. Any hint of discord evaporated when the Websters opened the door from their inner sanctum.

Glen Ridge, New Jersey was a small hamlet near Manhattan. Families were close knit, and the children all grew up together. Vacations and holidays became community affairs. The Websters’ Georgian home was tastefully decorated, but a bit out of date. However, any connoisseur noticed the expensive paintings on the wall and the gold and silver trophies of prestigious regattas and thoroughbred victories at the track. A very large, round diamond on Eleanor’s finger fractured the light into a rainbow of color, brightening her otherwise bland attire. Wealth and status were an important part of the image but carefully displayed without being garish. George and his offspring all wore gold signet rings as if the circles identified exclusive membership in the clan.

George was the first to come down the curved staircase prepared for his upcoming trip. He double-checked his travel itinerary taped to the refrigerator. After loading the wagon, he headed straight back to the house to pour a distilled beverage over the cubes in his glass. He tapped his fingers to the beat of Gilbert and Sullivan tunes as he waited for his entourage to assemble. A sport coat, flannel trousers, and a Brooks Brothers tie completed the uniform George always wore to neighborhood fetes. The standard garb was a multipurpose wardrobe suitable for the theater, parties, or travel. Any acquaintance could anticipate the patriarch’s attire with certainty. George and Eleanor had developed their predictable patterns when they met working for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the early 1950s. Attention to detail, subdued outward behavior and dress to avoid drawing unwanted attention, planning to the point of obsession, contingencies, and secrecy were all part of the intelligence mindset. The ladies were ready to go. George slipped on his dark overcoat and loaded Joan’s suitcase and tote bag into the back end of the wagon.

“Fundador,” George announced with a single clap and then rubbed his hands. The buzzword was a call to attention.

Two family friends hosted small holiday gatherings that Saturday evening. The Joys and the Wittpenns warmly welcomed the Websters into their homes. By the time he hung his coat, the bartender had George’s beverage ready and handed him the tumbler. The scene repeated itself when the family moved on to the next party. These social gatherings were regular affairs, a chance to catch up with everyone before going off in their own directions. The younger generation clustered and exchanged their latest endeavors. Joan’s friends fully expected to hear good reports about her accomplishments at Harvard; things were going very well at school. Joan was upbeat and her normal, bubbly self. Her giggle was infectious, and her smile lit up the room. Anne was the quieter of the two sisters, but Joan’s enthusiasm buoyed them both. Joan held a warm cup of grog, a traditional holiday punch served by the Wittpenns.

Eleanor was in another gaggle of guests boasting about her offspring and dropping names to amplify the importance of her children’s successes. She was insecure. She had very humble beginnings; she was conceived out of wedlock. Her parents married, but the calendar was too short to disguise her inception. In her generation, the branding of illegitimate unfairly inflicted shame on a child, which Eleanor carried deeply within her soul. Her parents divorced when she was a young girl. The estrangement from her birth father lasted for the rest of her life. Her mother remarried, and the new husband adopted 14-year-old Eleanor and her younger sister as his own.

After graduating from Mount Holyoke College in 1948, Eleanor married Thomas Hardaway, a West Point Lieutenant. Thomas called his wife Terry, a nickname Eleanor embraced to distance herself from her shame. Her happiness didn’t last long. Thomas was killed in Korea in 1950. Loss became part of Eleanor’s existence. Soon after Thomas died, John Selsam, her stepfather, passed away.

Eleanor moved to Washington, D.C. to work for the CIA. She met George in the agency, a charismatic man raised in the circles Eleanor envied. He had attended Taft Boarding School, Yale, and had a brief stint at Harvard before joining the Merchant Marines during the war. George’s father was a wealthy, prominent businessman who raced thoroughbreds and wintered with the elite in Palm Beach, Florida. The young widow grasped her brass ring tightly. George and Eleanor married on May 16, 1952. Two lives, poles apart, merged into one and formed their foundation on intelligence training. Doors finally opened for Eleanor; she guarded her station.

George swallowed one final gulp of his cocktail and announced the family’s departure. He slipped on his coat and kept his flock on schedule. In the car, George strangely broke with his normal routine. It was customary for George to make airport runs himself, solo, but this journey was different. Their house was only minutes away, an easy stop to drop off Eleanor and Anne before driving Joan to Newark Airport. After all, Anne had a long drive back to Boston the next day. Instead, Eleanor and Anne rode along to bid farewell to Joan. On the cold November night, the heater fan circulated a strong whiff of alcohol through the car, but George didn’t relinquish the wheel. Eleanor didn’t drive after dark, but Anne could have obliged if that was the reason to bring them along. The Websters never did anything without planning or purpose. The most logical explanation for Eleanor and Anne to ride along to the airport was for the drive home if George was not in the car.

George tapped his fingers on the wheel replaying the performance the family had enjoyed last night. He pulled up to the curb for departures at the Eastern Airlines Terminal still humming “Oh, Men of Dark and Dismal Fate.” He unloaded Joan’s bags, placed them on the curb, handed her money for a cab, and kissed her on the forehead. Joan turned to her family with a broad smile and waved goodbye before clutching her assorted belongings. Unsuspecting, she turned and walked toward the gate.

In a dark mind, the task at hand was simple.

Simple, Safe & Secret is available now from Genius Books.

👉 Click here to get the book