🚨 First Chapter Feature: The Crater Lake Murders

By Monty Orrick Deconstructing tragedy in one of America’s most enduring unsolved crimes

📬 **Email Preview Only**

> In 1952, two General Motors executives were murdered in Crater Lake National Park. The case remains unsolved—but the mystery has never faded.

👇 Scroll down to read the full first chapter:

**Deconstructing Tragedy** by Monty Orrick

In 1952, two General Motors executives were murdered at Crater Lake National Park. Their case has never been solved.

What happened that day still haunts the mountain.

In this gripping first chapter, author Monty Orrick dives into the FBI files, personal accounts, and long-forgotten clues that make up one of the most complex—and overlooked—cases in true crime history.

📖 Read Chapter One: Deconstructing Tragedy

The seldom seen FBI report is the official document concerning the senseless murders of two General Motors executives in Crater Lake National Park on July 19, 1952. Exhaustive in its scope, the 2,137 page report is a window into history where one may see a different way of life, looser standards of law enforcement and blatant racial prejudice; but a lot of professionalism too and in many areas great attention to detail. The sum makes a fascinatingly complex story, unique to its time.

The file is a historical document. Ninety percent of it is dated from two days after the murders in July 1952 through 1957. It is entirely of its time. The language is, in many places, baroque and dated—like a character from the past, speaking a little too elaborately.

There are few people with a living memory of the Crater Lake murders. Reading through the file, one is reminded that every person whose name appears has passed away. Conversely, the places where the crime occurred, a busy canyon overlook and adjacent patch of woods, look almost exactly as they did seventy years ago. Neither has the unfairness of the crime aged either. The murders are as shocking now as they were then. The injustice done to the victims’ families by never prosecuting or even naming a suspect has not diminished. In fact, it gets worse because everyone familiar with it assumes the case will never be solved.

Despite the bygone era, the futility in solving the murders, and the inevitable passing of everyone with personal knowledge about the case, there is an enduring curiosity. In all these years, only two people, the granddaughter of one of the victims and the author, have read the entire contents of the file. If that makes it sound intriguing, it is not. The story is damned interesting, but the file is mostly perfunctory reports, valueless interviews, negative ballistics reports, and descriptions of suspects lacking motive, means, or opportunity. The FBI file is not a page-turner. But to this writer, who has read it many times, it contains the outline of the greatest true crime story ever told.

Credit the bureau, who put everything they had into the investigation and extended enormous reach to solve it. In the first two months alone, over eighty agents’ names were attached to the case—working it hard. Though they never produced a suspect, it was not for lack of trying. The net was cast widely—into nearly all fifty states, Canada, and Mexico. Before long, they had gathered the names of over a hundred potential suspects. The report is a rogues’ gallery of all the most active criminals in America from 1952 to 1955, big time and small. Eventually, over two hundred individual names appeared in connection with the case; most were men with a criminal record. Surely someone in this group must have known what happened or was present at the murder. How did they avoid being caught by the most well-equipped law enforcement agency in the world at the time? And the largest question… Who did it?

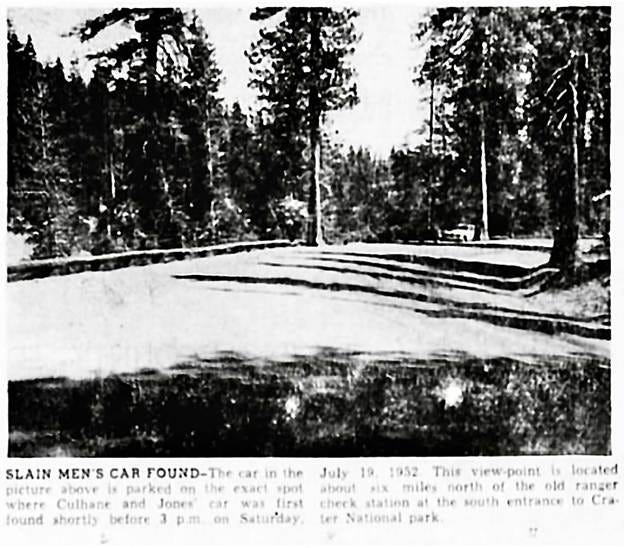

Whether you want to look at the Crater Lake murders through the historical lens of the FBI file or a contemporary “likeliest explanation” theory, the starting place for both is the same, the victims’ car.

… at a lookout point, they found the car used by the victims and on checking same found the key in the ignition, left front door open, the luggage and suit coats of both victims in car [sic].

FBI file. Volume 1 p. 1

How It Started

The above passage describes the moment that Saturday afternoon when Jack Vaughn, Frank Eberlein, and his 13-year-old son, Alan, drove up to the victims’ car. Though they didn’t know it yet, they were present shortly after the darkest moment of this mystery. The murders had occurred two hours earlier and half a mile away. The passage also represents the first of two great coincidences in this case. (The second comes at the end of the book.)

Before finding the Pontiac, Eberlein and Vaughn had completed their work week at Specialized Service, a busy automobile parts distributorship in Klamath Falls owned by Eberlein. That same morning, they had a short meeting with two General Motors executives visiting from out of town, Charles Culhane and Albert Jones, who had arrived neatly attired in suit and tie. They were on a business junket, visiting all the big accounts, including Specialized Service. Jones was the western regional manager out of Berkeley, California. He was a friend and frequent fishing partner of Frank Eberlein. Culhane was Jones’ big boss out of Detroit, the General Sales Manager for many of GM’s most important manufacturing parts. Before the meeting broke up that Saturday around 11 a.m., they all agreed to meet that afternoon at Union Creek just outside Crater Lake National Park where they’d spend the weekend fishing.

After leaving Specialized Service on Saturday morning, Jones and Culhane returned to their hotel and checked out, leaving Klamath Falls at exactly noon. On their way to Union Creek, they planned to drive Jones’ spacious Pontiac Chieftain around Crater Lake. Jones had made this tour before, including a few weeks previously with his wife. This was Culhane’s first visit to Crater Lake and he was looking forward to it and the tour with Jones.

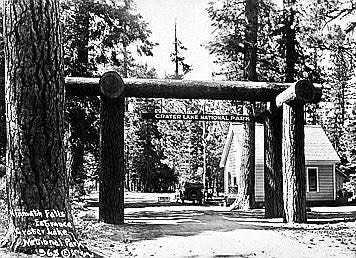

Vaughn and the Eberleins left town around 1:30 p.m., planning to drive directly to the cabin. According to weather reports, it was a glorious afternoon with summer temperatures in the seventies. Alan can still remember the day and the vehicle they drove, a 1948 tan Chevrolet pickup. Seated between his father and Vaughn, who was driving, they entered the park through the old south gate then referred to as the Klamath Falls entrance. Vaughn produced a season pass for Ranger Joe Hunt who had just arrived for his shift and waved them through.

Three miles up the road and a few minutes later, they recognized Jones’ Pontiac parked at the overlook. Vaughn steered his truck beside it. Everybody got out expecting at any moment to see their friends walking along the trail or from behind the huge Ponderosa pines that lined the canyon rim. The Pontiac looked like it had just been parked there. The right passenger door had been left open. The car keys hung absently in the ignition. Their suit jackets were carefully folded on the backseat. Surely, Jones and his boss were nearby.

In this state of anticipation, the minutes ticked by. A dramatic precipice dropping a football field’s length into the canyon formed by Annie Creek was just a few feet away—distracting and beautiful, attracting more cars and tourists to the overlook. The cool mountain air was fresh and scented of dirt and pine needles. Time passed quickly until, after forty-five minutes or so, one of the men realized something was dreadfully wrong. Their friends should have shown up by now, with a smile on their face and a story to go with it.

Less than an hour after they arrived at the park entrance, Frank and Jack returned to the south gate to inquire about their missing friends. Surely, there was some reasonable explanation. Misfortune could not visit two respectable businessmen touring a busy park in July. There wasn’t enough time for trouble to have found them. The men had only been in town for a day.

Their Last Full Day

The day before was Friday, July 18, 1952. Albert Jones and Charles Culhane met in Klamath Falls to finish a business trip Culhane had begun that Monday. Though they had spoken over the phone to arrange their meeting, Jones and Culhane had never met in person before. Both men worked for the General Motors subsidiary, United Motor Service. Though it has since merged with AC Delco, this important division of General Motors produced and sold Delco batteries, AC spark plugs, and other GM parts. In 1952, General Motors was the largest automobile manufacturer in America.[2] Chevrolet was their most popular make. Culhane had been General Sales Manager for a little over a year. Responsible for sales throughout the United States, Culhane worked and resided in Detroit, Michigan but had never traveled west before in this capacity for UMS.

Jones was Zone Manager for the UMS office in Berkeley, California—a position he’d held for several years, responsible for accounts from Northern California to Southern Oregon. He’d worked for UMS for fifteen years in total. Before his trip with Culhane ended, they planned to visit Medford on Monday then drive to Eureka in Northern California and end up in San Francisco by Tuesday evening. Jones would drop Culhane off at the Fairmont Hotel on Nob Hill where his boss would spend the night before returning to Detroit the following day. After dropping off Culhane, Jones would drive across the Bay Bridge to his home in Concord. He lived there with his second wife Betty with whom he’d been married for a little more than a year.

Outside of work, the executives were very different people. Charles Culhane was from the Midwest, a dedicated family man who’d risen quickly at UMS to a senior position. A private person, Culhane had few outside interests. He was not known to associate much with coworkers outside the office.

Jones’ attitude and lifestyle was altogether different. He’d been divorced. He was a Westerner with city tastes he’d cultivated living in San Francisco. He was gregarious at work and play—with a reputation as a man about town. Born in Canada, he changed citizenship when his family moved to Washington state. His upbringing in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest gave him an appreciation of nature and wilderness. He was comfortable in the outdoors and went out of his way to explore them whenever his busy schedule permitted. Among his outdoor skills, Jones was an avid, skilled fly fisherman.

Another difference: Jones and Culhane were physically dissimilar. Autopsy records show Culhane was thin—five feet eleven inches tall and one hundred sixty pounds. Albert Jones stood about six feet and one inch tall. He weighed two hundred and ten pounds. The medical examiner described him as “a very large man.”

Flying in from Detroit, Culhane’s first stop on Monday was Spokane. For the rest of the week, he was driven throughout the state by Seattle Zone Manager Harold Weirs. After a whirlwind tour visiting parts shops and big distributors, the two men eventually made it to Eugene, Oregon on Friday. The weekend had finally arrived, but work wasn’t over yet. Culhane was scheduled to meet Al Jones in Klamath Falls the next day.

It is a scenic two-hour drive from Eugene east to Klamath Falls. Up and over Willamette Pass, several unique Cascade features catch the eye of motorists on Highway 58. As Weirs and Culhane motored past, they could not have failed to notice Diamond Peak’s jutting cone and deep, shadowy bowls filled with snow even in July. The snowmelt feeds Salt Creek which falls steeply down the mountain then, beside Highway 58, tumbles suddenly over sheer obsidian falls, 286 feet high. On the other side of the pass, the highway snakes around Odell Lake, another showcase for Diamond Peak. Motorists who stop beside its ample shoreline—on clear days when the water is still—can admire the peak’s reflection in the lake.

Perhaps Culhane and Weirs stopped to look at Diamond Peak—the weather that day was clear—or, after a long week sleeping in hotels and being introduced to strangers, Culhane may not have paid much attention to his surroundings. On the last full day of his life, Charles Culhane may have simply looked forward to reaching Klamath Falls and getting some rest. He would complain the following day of feeling fatigued.

While Weirs and Culhane were driving over the pass, Jones drove north from the Bay Area in his company car, a light green 1951 Pontiac Chieftain. Among its features was a “268 straight 8” engine and Hydra-matic four speed transmission—a nice automobile for touring. Jones used the main highway through the state’s Central Valley—old U.S Route 99. Like the interstate that replaced it in 1964, 99W was a straight shot. Jones stopped briefly in Redding, California to visit a client before heading east to Klamath Falls. The trip took all day.

The Klamath River drains an enormous basin, the Klamath Basin, extending from Crater Lake south and west into California. After flowing two hundred and sixty miles, the river empties into the Pacific Ocean by Requa. Another important feature of the basin is the Pacific Flyway, one of the planet’s greatest bird migration routes. Besides the Klamath River, other local waterways that attract the birds are the Williamson River, Upper and Lower Klamath Lake, Agency Lake, and the Sprague River. All of these and seasonal creeks too numerous to mention feed enormous marshes which historically filled vast areas between the rivers and lakes. An enduring legend of this place is that in spring and fall millions of ducks, geese, and migrating waterfowl would cover the sky until the blue and bright sun behind it was no longer visible.

The most prominent feature in this area of the basin is Mount Scott to the north, almost 9,000 feet high. To the near side of Mt Scott is a smaller, darker mountain, deceptively insignificant. In fact, it’s the epicenter of one of the most important events in recent geological history. This dark mound near Mount Scott was hollowed out by a cataclysmic volcanic explosion 7,700 years ago. Previously, this mound was a mountain, among the tallest in the Cascade Range, Mount Mazama. When a restless mass of gas and molten rock trapped below the mountain could no longer be contained, it exploded. Mazama’s liquid core covered the area in lava flows and deep deposits of ash. Rocks from the blast were flung clear to Medford. A silica cloud created during the event reached all the way to Quebec in Canada. When the ash, lava, and noxious gas cleared, there was a big steaming hole or crater where the mountain had stood. Eventually, the crater cooled, and after thousands of years, filled with snowmelt—a lot of snowmelt. The lake that formed is almost two thousand feet deep. Renowned for its clarity, depth, and emerald blue color, Crater Lake is the most beautiful lake in Oregon; also, its only National Park.

Friday Evening in The Falls

In 1952, the nearest town with accommodations for tourists visiting Crater Lake National Park was Klamath Falls. This is where the three executives met on Friday, July 18th. Weirs and Culhane arrived first, then Jones. They all checked into the Wi-Ne-Ma Hotel downtown. From the hotel, Jones called Specialized Service to set up the meeting for the next morning. In his fifteen years at UMS, Jones visited Specialized Service several times a year and had struck up a close personal friendship with Frank Eberlein. During the season and when they weren’t doing business, the men enjoyed fly fishing the trout streams around Klamath Falls. Besides talking business and meeting Culhane, plans were firmed up for the weekend and where they would fish.

The fishing opportunities would be excellent. The snowmelt and flows had come down after the spring runoff. The weather was warm and the bugs were out. Perfect conditions for fly fishing. They’d fish Union Creek outside Prospect just west of Crater Lake, and stay at Union Creek Resort. Hopefully, the big boss would join them.

Sometime before five o’clock, Jones drove to The Gun Store on Main Street. He spent $15.33 on a fishing license and some tackle. The out-of-state license was $5. Whatever else Jones bought, it likely included a few Bucktail Coachman flies. These were Frank Eberlein’s favorite flies for the waters they would ply with hook and tackle.

One last detail of Jones’ trip to The Gun Store is mentioned briefly in the FBI file. Frank Eberlein recollected in one of his many interviews with the bureau that Jones’ boss, Charles Culhane, accompanied him during his visit to The Gun Store. This small detail is inconsistent with the FBI file that has Culhane and Weirs arriving in Klamath Falls around 6:30 p.m. A Gun Store employee said Jones came in alone.

That evening, Jones, Culhane, and Weirs enjoyed a drink together at the hotel. After that, Weirs went out around eight to visit friends in town. Jones and Culhane stayed in and had dinner. When Weirs got back around midnight, he stopped by Jones’ room for a nightcap.

In his interview, Weirs said he did not notice anything unusual that night or the following morning. All three UMS salesmen went to bed that night without any premonition about what would happen later that day.

Saturday July 19, 1952

Early Saturday, Weirs headed back to Seattle, leaving Jones and Culhane to finish the trip.

After breakfast, they made two quick business stops in Klamath Falls. The first was to Moty and Van Dyke, a repair and parts shop. Culhane gave their top salesman a special pin with a Delco battery insignia. Around 10:15 a.m., they went to Specialized Service to meet Frank Eberlein. Sales manager Jack Vaughn was also there. Vaughn was Eberlein’s top man and a close friend. He was also friendly with Jones. On a previous visit, Jones had joined the Vaughns for dinner in their home. Vaughn would be the third member of the fishing party that weekend. Like Jones, he made plans to stay at the Union Creek Resort.

The resort is still there today and, like so many places in this story, remains virtually unchanged. Just west of Crater Lake on Oregon Route 62, Union Creek flows under the highway near the resort. The creek boasts of some of the best small water trout fishing in the state—then and now. Frank Eberlein was particularly enthusiastic about the dry fly fishing in Union Creek—one of many feeder streams of the Rogue River. Jones’ favorite Rogue River tributary was Foster Creek, a few miles away. Besides the Rogue River, the north fork of the Umpqua is also in the vicinity. It is a world famous steelhead destination, popularized in the early 20th century by the western writer Zane Grey. The resort is still popular with anglers.

All of these fisheries have a special charm, especially the smaller and less preferred fisheries like Union Creek. Seldom deeper than a few feet and easily waded across, each is a little different from the other and can hold the imagination of a trout fisherman for as long as the spell lasts. The pine forests they twist through are full of impressive, large trees. In July 1952, the snow was off the ground and the rivers had just come down, ideal conditions for fly fishing. Lurking under the cutbanks and in the deeper pools, colorful rainbow trout called redsides are fairly numerous and occasionally grow quite large, exceeding two pounds or better. The specific knowledge required to catch them on a fly is limited to locals and the occasional out-of-towner who knew his stuff, like Jones.

While Jones was thinking about the trout fishing he’d soon enjoy, his boss was preoccupied with work.

One reason for Culhane’s coming west was to examine how business was being conducted. He had recently expressed dissatisfaction about excessive travel expenses being charged to the company by salesmen like Jones. Jones’ regional manager, Ira Kennedy, was taking the brunt of Culhane’s dissatisfactions regarding the bottom line. The FBI interviewed several people, including Culhane’s wife, who said Kennedy and her husband did not get along. This may have put Jones in a good position. The several days of travel to get acquainted with Culhane might have been an opportunity for Jones’ promotion, depending on the boss’ level of dissatisfaction with Kennedy.

However much Jones wanted to make a good impression with his boss that weekend, it was not going to happen. At some point Friday or Saturday, Culhane complained of not feeling well and elected not to join the fishing party for the weekend. Perhaps he was just tired. From Jones’ room in the hotel on Friday, Culhane called the exchange. The operator connected him to the Hotel Medford where he made his reservation for Saturday and Sunday.

Culhane was not the type of boss who enjoyed dry fly fishing or drinking and relaxing in a mountain cabin with coworkers. According to his wife, his one personal indulgence was visiting museums on the only day he reserved for himself, Sunday.

So the new plan for Saturday was that Jones would play tour guide and drive Culhane to the lake and possibly around it. After that, Culhane would take the Pontiac and head straight to Medford— dropping Jones with his host at Union Creek along the way.

Jones must have been a little disappointed. He would not have the chance to schmooze his boss around the fireplace or show off a bit, casting flies to big hungry trout. It would just be the four of them: Jones and Vaughn, Eberlein and his son, Alan, fly fishing for trout in idyllic surroundings—with nothing to bother them until Monday morning when Jones planned on taking the bus from Klamath Falls to Medford to meet Culhane there.

In a three page, single-space account he wrote about the events of July 19th, Frank Eberlein described it this way:

Since their next appointment was in Medford on Monday, they decided to do some sightseeing since Culhane had never been out West. Jones was familiar with the area around Crater Lake and Union Creek, having spent some vacation time in the area previously.

Frank Eberlein

The Crater Lake Murders of July, 1952

A Beautiful Tour

1951 Pontiac Chieftain

That was how they left it on Saturday at the offices of Specialized Service. It had been a long week, especially for Charles Culhane. Everyone was looking forward to enjoying a little time off, each in their own way. It was a beautiful summer day—almost seventy degrees out. No one could know the goodbyes they shared were final when Albert Jones and Charles Culhane drove off in the Pontiac at 11:15 a.m.

After they collected their bags and left the hotel, their last stop in Klamath Falls was for fuel, recorded on a gas station receipt totaling $3.83 at 12:01 p.m.

After filling up, Jones gripped the column shifter in the Pontiac and put it into gear. From the gas station, he drove north through town. The trip from Klamath Falls to Crater Lake begins unremarkably, but the scenery improves quickly. In an hour and a half, it is possible to drive to the edge of an enormous steep-sided bowl filled with water bluer than the sky.

Crater Lake was their destination, but the only lake they would see that day was Upper Klamath Lake, the largest lake in Oregon. Highway 97 curved around thirteen miles of the eastern shore, affording a view west to Mount McLoughlin, over 9,000 feet high. The smell of desert sage was in the air. If the windows had been cracked, for an Easterner like Charles Culhane, this would have been a unique sensation—the pleasant sting of sharp, desert perfume.

The big Pontiac roared down the road. Inside it, they rested on a commodious bench seat with heavy springs and deep padding, but no seat belts—not in 1952. The polished enamel dashboard was inset with an ashtray and cigarette lighter. Radio sounds emitted from a round speaker with a clock inset. An almost empty carton of Parliaments lay on the seat between them, in case either man needed a fresh pack.

Highway 62, approaching CLNP south gate

A few miles north of Upper Klamath Lake, they would have crossed one of its main tributaries, the Williamson River. Spring fed at its source, it drains almost two million acres in fifty miles before being consumed by the lake. By mid-July, after the heavy winter of ‘51-‘52, the Williamson was just coming into shape. The fly fisherman in Jones likely took a quick look over his shoulder driving over the bridge.

Somewhere between leaving Specialized Service and reaching their final destination, both men removed their coats, folded them neatly and placed them on the backseat. This simple action has always stood out. Common to disappearances or untimely deaths, small acts performed in the last hours appear larger. A bath drawn, but never taken. Or a sport coat laid out smoothly to avoid wrinkles, but never worn again.

Just past the river, Jones read the sign for Crater Lake National Park. The big steering wheel turned easily in his hands as the Pontiac left the main highway onto Oregon Route 62. Within a few minutes, they were in Fort Klamath whose most famous resident has been dead since 1873.

Captain Jack, or Kientpoos[3] to his people, is the famous Modoc warrior whose tribe inhabited what geographers call the Intermountain Region of California—from Mt Shasta to Tule Lake. They lived here from time immemorial until the 1870s. At that time, the federal government decided they needed to be moved north to cohabitate with the Klamath Tribe. When the Modoc would not be moved, a war broke out. Many died in this conflict, shot, or in Kientpoos’ case, executed. His headstone and three other monuments bearing the name of Modoc warriors mark the spot. When Jones and Culhane wheeled past it on the left, they were only a few minutes from the Klamath Falls entrance to the park.

They made pretty good time. After their gas stop in Klamath Falls, it only took an hour and four minutes. Hindsight suggests haste may have led to their undoing. Had Jones decided to wet a line at the Williamson Bridge, their entire future might have changed in those few minutes. Since Jones apparently drove as fast as he could, they could not have arrived much sooner. Had they driven just a few minutes slower or stopped anywhere on the way, their day and lives may have gone as planned.

Slowing to pass through the Klamath Falls entrance.[4] Jones bought a day pass for a dollar. Just like tourists entering the park today, he received a sheet filled with park information and a map of the lake. In 1952, it was called the Crater Lake Bulletin. Jones put the Bulletin on the seat next to the Parliament carton. The ranger jotted down his license plate number and the time of day.

When pressed later by the head ranger and FBI, Dick Marquiss could not remember who was driving the Pontiac or give any details of their meeting. In fact, he did not remember anything about the men or their vehicle. They arrived at the end of his shift and before his replacement, Joe Hunt, took over. The best Marquiss could recollect was that he did not notice anything suspicious around that time. During the exchange, Marquiss read Jones’ round-cornered, gold-on-black California license plate and wrote the number in his log, 6A16762. Next to that, he wrote 1:05 p.m. He issued them a permit, 49803. Though he never remembered anything, Marquiss was almost certainly the last person who saw Jones and Culhane alive, aside from their killers.

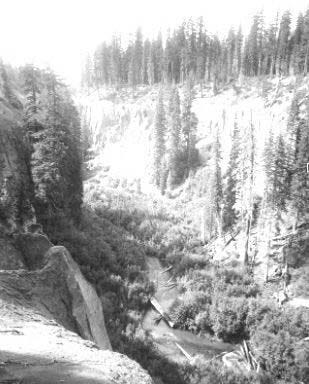

Three and a half miles uphill from the old Klamath Falls entrance to the park is a viewpoint, the Annie Creek Canyon Overlook. It is the first remarkable view tourists come upon inside the park. Here, tourists look across a chasm to the opposite side—a 90° cliff face of gray, volcanic ash. What most don’t realize is that they are standing on a cliff face equally extreme. If you’re brave enough to stand at the edge, you can see all the way to the bottom, three hundred feet down. There, the tiny creek that carved this steep, narrow canyon meanders through a strip of willows and trees fallen down from the canyon above.

There are several turnouts on the highway along Annie Creek Canyon. The first one inside the park is the overlook that figures in this story. Today, it looks almost exactly like it did in 1952. Its surface is unpaved. The dirt is smoothed every season by thousands of tourists and their vehicles. More recently, a paved strip was added—near the highway. In 1952, there was a low wooden barrier along parts of the perimeter near the road, but that has since been removed. Other than the old fence and the paved pullout lane, nothing else has changed in more than seventy years. The Annie Creek Canyon Overlook remains most tourists’ introduction to Crater Lake. A preview of the coming attraction.

A photo that accompanied a ten-year retrospective of the Crater Lake murders in the Medford Mail Tribune on October 11, 1962.

The overlook and the dirt parking area next to it appear almost ordinary from the highway. But there is something about it, a tiny temptation. It beckons for one to come closer and see what all the excitement’s about. That is why a thousand people stop here every week during the season. They get out of their cars, take a few steps, and the sudden, precipitous edge comes into view. This is where parents freeze and look around nervously for their children. The brave among them step closer. People with a fear of heights never get out of the car, sensing the danger. You don’t see a three hundred foot straight drop every day—not with dirt under your feet.

Compared to the Grand Canyon and the ancient processes that created it, Annie Creek Canyon is a newborn. Seven thousand years is a geological blink of the eye. The canyon walls are devoid of any horizontal lines or strata representing different times in prehistory. There is only one layer—representing one moment—when Mt Mazama exploded into the stratosphere and Crater Lake began forming. But most tourists don’t think about that. They just know it’s steep as hell and to keep a tight grip on the kids.

When the tourists clear out, it’s easy to imagine Jones and Culhane pulling up in the big Pontiac… slowing as it turned off the highway, dirt crunching under the polished whitewalls. Rolling to a stop, both doors swung open and the men stepped out. Inhaling the cool mountain air, they ambled in the direction of the overlook—exactly like a hundred other park visitors that weekend. Or this weekend.

But what happened next to Albert Jones and Charles Culhane? No one knows.

The First Great Coincidence

After Jones and Culhane drove away from the gate at the Klamath Falls entrance in the direction of the lake, they effectively vanished for two days. What happened next in the timeline at the overlook is truly fantastic. According to Alan’s recollection all these years later, Vaughn was driving when the pickup arrived at the overlook. They parked beside the Pontiac on the canyon side.

Frank Eberlein described the moment in a paper he penned about the dramatic events that weekend.

. . . much to our surprise, we came upon the Jones Culhane car. The right front door was open, the keys were in the car, and everything in the car appeared to be in order but no passengers were in sight. We assumed they must be nearby so we waited for them to appear.

Frank Eberlein

The Crater Lake Murders of July, 1952

It was incredibly good luck when Frank Eberlein and Jack Vaughn saw Jones’ Pontiac parked beside the road at the overlook. Fortuitous, if they could take advantage of their good timing and find their friends, which seemed possible. If they had not noticed Jones’ car on their way to Union Creek, who knows how long it might have sat there before someone looked for the owner.

The only connection to them was their car. It was always one of the first items mentioned in law enforcement reports and newspapers. The unhurried way the Pontiac was left at the overlook created as much mystery as the men’s disappearance. This seemingly abandoned expensive automobile became the centerpiece of the search and every story about it.

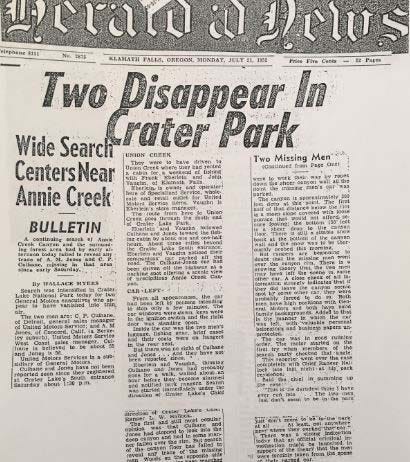

The first newspaper report appeared Monday July 21st in the local paper and it focused on the Pontiac. This was two full days after Jones and Culhane had disappeared. The newspaperman got a few details wrong, but you can’t blame him. He was describing something he hadn’t actually seen. Plus, the Pontiac had been moved by then. Nevertheless, the description had a matter-of-fact immediacy.

The Abandoned Pontiac

From all appearances, the car had been left by persons intending to stop only a few minutes. The car windows were down, keys were in the ignition switch and the right door was standing open. Inside the car was the two men’s luggage, fishing gear, briefcases and their coats were on hangers in the rear seat.

But there was no sight of Culhane and Jones…. And they have not been reported since.

Wallace Myers

Klamath Falls Herald and News, p. 1

The FBI and Oregon State Police reports detail exactly what was inside the car. In the backseat, the men’s suit coats were neatly folded alongside their luggage—not on hangers. There was a Brownie camera too, but no film was inside it. Jones had his fly-fishing gear in the back with a copy of the latest Sports Afield. In the middle of the front bench seat lay a Parliament carton with two packs inside, and the Crater Lake Bulletin.

The Pontiac was in a completely undisturbed state, at least according to John Vaughn, but he saw something out of place.

VAUGHN stated that as they were examining the tracks of the victims’ car, they noted tracks which appeared to cross the tracks of the victims’ automobile, and it would appear that this car had made a fast start as the gravel on the shoulder was dug up some. The left front door of the victims’ car was closed tightly.

FBI File, Vol. 1 p. 264

After driving through the Klamath Falls Entrance to the park at 2:20 p.m., the Eberleins and Vaughn arrived to find their friends’ unattended vehicle parked at the overlook. After waiting another forty-five minutes or so at the overlook, according to Frank, they “grew very concerned.” They had all been together in Klamath Falls just a few hours before. Now, with their car parked at the edge of a precipitous cliff, the two General Motors executives were nowhere in sight. Had their friends fallen into the canyon? Frank and Jack discussed this frightening possibility.

The old south gate or the “Klamath Falls Entrance” to CLNP through which Jones and Culhane entered and their killers likely exited.

Courtesy: Southern Oregon Historical Society

In the midst of all the confusion, one person had the presence of mind to attempt to determine how long the Pontiac had been parked. Thirteen-year-old Alan Eberlein pushed his hand through the open chrome grill to feel the radiator. Though it does not appear in the FBI or OSP reports, his father repeated Alan’s observation in his three-page statement. He said Alan (below) found the radiator “quite warm” when he touched it. It is a clue that confirms the accepted sequence of events—that the Pontiac had been there since Jones and Culhane entered the park. When asked about it sixty-eight years later, Alan Eberlein recalled the moment. Could the hot engine block of a 1951 Pontiac parked in a sunny spot on a warm afternoon remain hot to the touch after an hour and a half?

“That’s how we took the temperature of our farm equipment. It was a very warm day. The car wouldn’t have cooled down real fast.”

While Alan was taking the temperature of the Pontiac, his father and Jack Vaughn were realizing their friends might be in a lot of trouble. They climbed back into the tan pickup and returned to the Klamath Falls entrance hoping for some information that might explain everything.

Another ranger, Joe Hunt, had replaced Dick Marquiss since Jones and Culhane had passed through. He recorded the time when Eberlein and Vaughn arrived to report their friends missing. It was 4:40 p.m. Standing around the tiny south gate booth, Eberlein and Vaughn talked it over with the ranger then returned to the overlook at five o’clock. Between the time the men left and then returned to the Pontiac, something odd happened to Alan. It was a momentary event which, in the intervening years, has acquired some significance. Many believe the perpetrators returned to the scene.

After his father and Jack Vaughn left to find a ranger, Alan stayed behind to keep an eye on the luggage and gear. It was late afternoon. Shadows were lengthening across the parking area. He decided to wait in the car. Behind a steering wheel big enough for a tugboat, there was plenty of room on the wide bench seat. With nothing else to occupy him, Alan pulled Jones’ copy of Sports Afield from the back. Leafing through the pages, he became distracted by images of big game hunting, fishing scenes, and advertisements for the most modern fishing and hunting gear. Looking down, he ignored the hum of automobiles to his left entering and exiting the park. It was a brief interlude of calm in the upsetting afternoon. Suddenly, from the direction of the highway, Alan heard something that caused him to look up from his reading.

“A car came up fast, crunching gravel,” Alan recalled.

The vehicle pulled up very near the driver’s side window, but only for an instant, then drove off. According to his father, Alan “saw the taillight disappear behind the big pine tree.” The only piece of vehicle information he could glean from that fleeting moment was its color, black. The thirteen-year-old’s account is described in his father’s report.

Alan remained with the Jones Culhane car. He reported that while positioned in the driver’s seat of that car another car approached from the North, crossed over to the left side of the road, pulled alongside but instead of stopping, accelerated and continued South.

Frank Eberlein

The Crater Lake Murders of July, 1952

For our TV story in 2013, reporter Ian Parker and I interviewed Alan beside the overlook. He was seventy-four years old then. Could he recall who was driving the car that pulled up next to him at the overlook? During those crucial few hours after Albert Jones and Charles Culhane disappeared, could it be the perpetrators returning to examine the contents of their victims’ car? Alan was an uncommonly observant boy, but he never saw who was driving that day.

“It all happened… fast. By the time I looked up, the car was behind me. I saw it for a few seconds… then it disappeared behind this big tree.”

It took only a few seconds, but something had happened.

What did it look like to the occupant or occupants of the other vehicle? They were in a car driving southeast just before five o’clock. The sun would be behind them—below the trees, fully illuminating the overlook and the Pontiac. Looking in the direction of the other vehicle from the Pontiac would be looking towards the sun. It was an advantageous position for the car that approached the Pontiac and may explain why Alan didn’t see much.

The question is, why didn’t the other vehicle see Alan in the front seat before they pulled beside him? A thirteen-year-old boy hunched over in a large automobile behind a big steering wheel might be difficult to see—until they were side by side.

Many believe these were the murderers coming back to plunder the contents of the Pontiac. If so, it reveals a critical piece of information. They drove away from the overlook in the direction of Fort Klamath via the exit just down the highway.

No one knows what type of automobile the killers drove that day. Alan could not recall any distinguishing details of it, which suggests the car was not flashy or expensive. More likely, it was an older model and a common make, like a Ford or Plymouth. Anybody that needs money badly enough to rob two strangers inside a busy park is not driving a high-value automobile.

This plain old jalopy may not have belonged to the perpetrators either. They might have borrowed it. If it was registered to them, it was not one of the 466 vehicles recorded in the park that day and whose owners were interviewed as part of the FBI probe.

How did this mystery car avoid having its license plate recorded entering the park? Dick Marquiss recorded Jones’ license number when he bought a pass. Joe Hunt did not record Frank Eberlein’s license plate number because he had a pass, purchased earlier in the season. Besides pass holders many others could come and go without any record of it. Park employees, contractors working inside the park, and local tribal members all avoided having to pay a fee and have their license recorded. After producing a pass or identification that showed they belonged to any of the above, they got waved through—entering and leaving the park anonymously. It is also possible the driver of this mystery car entered with a pass he had stolen. Or he may have switched license plates. About 50 of the 466 plates recorded in the park on July 19th could not be traced. Finding every tourist driving through the park that day was impossible and the FBI knew that early on.

North Gate, East Gate and Klamath Falls Entrances in 1952

Snowpack measurements around Crater Lake National Park in 1952 reflected one of the heaviest winters on record. The west and south gate entrances were open all year. The road from Diamond Lake to the north gate was plowed and opened on July 12th. The road from the east gate into the park was plowed during the third week of July. It opened for the season on July 19th, coincidentally, the same day as the murders. The Park Service released the information where it was picked up by at least one local paper the day after.

MEDFORD (U.P.)—All entrances to Crater Lake National Park were open to two-way traffic Saturday and visitors facilities were in operation… the State Highway Department reported that snow clearing operations Had been completed on the north and east entrance roads. The north entrance had been open to one-way traffic for a week.

The Eugene Guard July 20, 1952 p.10

The east entrance was closed to traffic permanently in 1956—partly because it was the least frequented by tourists. Most visitors drove or arrived by bus via the north and south entrances because of their highway access. Locals living in towns east and north of the park along highway 97 preferred the east entrance. Anyone who used the east gate on the day it opened in 1952 was likely a local person, because that information was not widely known—for at least another day—until it appeared in The Guard. If one ascribes to the theory that a local person or persons did the murders, it would make sense that they used the east gate to enter the park that day.

The Search Begins

After Eberlein and Vaughn reported their friends missing to the Ranger Hunt, they drove back to the overlook. Eberlein and Vaughn were shortly met there by Chief Ranger Lou Hallock. This was not the Chief Ranger’s first search and rescue. Before taking the job at Crater Lake National Park, Hallock had been Chief Ranger in Yosemite and Carlsbad Caverns; both have had their share of visitor mishaps.[5] Logic dictated that the men had either gotten lost in the woods or fallen into the canyon. In either case, finding them quickly would increase their chances of survival if, indeed, they were in peril. Someone produced a map. To see the area from above, the canyon looks like a flat, gray snake. Running roughly parallel to it, Powerline Road is a thin dirt line scratched into the forest.

Hallock got things moving in a hurry. It was early in the evening when two search parties were formed. The first group consisted of a dozen or so men, mostly park employees, who walked together through the woods on the opposite side of the highway. There was much shouting of the men’s names and looking for anything that might stand out from the ordinary. The forest was extremely plain. Medium size lodgepole and fir rose to the shoulders of a few larger Ponderosa pines. There are no trails or landmarks whatsoever in this southern strip of the park. The southern boundary of the national forest is less than a half mile away. The only manmade feature here is a dirt road running underneath the power lines. It delivers electricity to this side of the park, including the headquarters and lodge complex. This one lane road is fairly maintained, but not marked. Its two entrance points are difficult to recognize from the highway. Because of the power lines, there was no reason to invite tourists in there. It was a no man’s land at the edge of the popular park—an empty corner. In the waning light of a bluebird day on July 19, 1952, it would see more activity than it ever had before.

Before the east entrance closed to all motor traffic in 1956, it was popular with locals visiting Crater Lake.

Courtesy: Crater Lake Institute

All the shouting and commotion implied that there was reason to believe the men might be out there, hopelessly turned around in the nondescript woods or walking on Powerline Road. This was the best case scenario.

The second big search that day was opposite the woods in Annie Creek Canyon, steep-walled and potentially dangerous for climbers. Searching it required a technical descent with ropes and a harness. Two rangers with special training were assigned. Their mission was to look for and, it was hoped, rescue anyone clinging to the canyon wall. Then there was the alternative: Climbers would recover Jones and Culhane’s bodies at the bottom of the canyon.

This grim, second outcome became the most favored theory among searchers that evening. It’s easy to understand why. The Pontiac was parked by the edge. The park had a history of deadly falling accidents. Awful as it sounds, mishaps involving two visitors falling simultaneously have occurred there.

It was possible one of the men had tumbled over the edge and the other, in an attempt to save him, fell too.

The man Hallock assigned to search the precipitous slope was Assistant Chief Ranger Bernie Packard. In the late afternoon, he and a climbing partner were lowered over the wall. Dangling from the edge, they combed the steep, loose ground looking for a man clinging to a shrub—just out of earshot or too tired to call out. Eventually, they descended the entire three hundred feet.

At the bottom of the canyon, they found themselves standing next to a boisterous stream barely a foot deep and several feet wide, Annie Creek. They spent the rest of the late afternoon and evening searching the ground between the walls. There was a lot to search: melting snow drifts and the waist-high strip of willows lining the creek. For Packard and his partner, they were ready to find two lifeless bodies down there somewhere, but that did not happen.

After a few hours it began to grow dark. The sun set around 9:00. There was no moon. The canyon darkened until the only thing visible from the bottom was the starry night sky between the walls. All that met the senses down there, besides the starlight, was the constant, low gurgling of the creek. The climbers were forced to quit. Preparations were made for them to stay overnight.

… because of the hazard involved in retracing their steps in the dark… Bedrolls and food were lowered to the party and they bedded down for the night.

Chief Ranger Lou Hallock,

REPORT OF MURDER OF C.P. CULHANE

AND A.M. JONES IN CRATER LAKE

NATIONAL PARK ON OR ABOUT JULY 19,1952

Back at the rim, a searcher turned the keys in the Pontiac’s ignition, to see if it would start. The six-cylinder engine turned over immediately. Car problems did not contribute to the men’s predicament. Neither did they run out of gas. The fuel gauge registered full.[6]

That evening Jack Vaughn phoned his wife in Klamath Falls and asked her to check the two area hospitals. Neither had admitted Jones or Culhane.

The old Park Headquarters where Frank Eberlein and his son, Alan, spent the night of July 19, 1952. Today it’s an administration building, part of the complex that includes the visitor center.

Courtesy: NPS

Unlike the canyon search along Annie Creek, the ground search by the highway was not technical. The volcanic, sandy ground does not support much vegetation between the trees, which are not dense. Sight lines are good. The ground here slopes several degrees downhill in a southerly direction toward the park boundary on the other side of Powerline Road. At least, that is what it looks like in 2022.

It’s hard to know exactly how these woods appeared seventy years ago, but photographs of the area taken around 1952 look indistinguishable from today. Many features would not have changed at all, like the ground slope or the composition of the larger trees.

In these sparse woods beside the overlook, there are two small, several acre sections of older, larger trees. One lines the highway opposite the overlook. It gives the impression that the woods hereabouts are dense and beautiful, which they are not.

The second woodsier area is a quarter mile from the highway. From ground level, it does not stand out from the woods surrounding it, but when viewed from overhead, a slightly greater density of trees is apparent. This second stand was a little farther than crews could reach before it got dark on Saturday.

Eventually, all the searchers except Packard and his partner returned to a staging area on Highway 62. The missing men were still presumed lost or fallen into the canyon. Nothing about the Pontiac indicated a crime had been committed, or any violence either. Jack Vaughn drove Jones’ car back to Klamath Falls in the hope that it would be returned to its owner the following day. Frank Eberlein and Alan drove to the Park Headquarters where a core group planned for Sunday. The Chief Ranger described their deliberations that night.

A discussion was held in the Ranger Office… in an attempt to find a possible solution to the disappearance of Jones and Culhane…. It was decided to reinstitute the search shortly after daylight enlarging the area examined as the search progressed. Early Sunday morning the party in the canyon researched the area of the canyon floor immediately beneath the overlook. They then proceeded upstream and searched an additional one fourth mile of the canyon floor. The search parties on the West side of the highway were enlarged and continued the search of the forest land North and South of the Overlook. A portion of the area searched by these two crews had been previously searched late Saturday afternoon and the duplication was purposeful in order that no possible clue be overlooked.

Chief Ranger Louis M. Hallock

REPORT OF MURDER . . .

That evening, Frank Eberlein called UMS Area Manager Ira Kennedy in San Francisco. Kennedy had worked with Al Jones for many years. They were friends. After receiving the call from Eberlein that the men had gone missing, Kennedy attempted to book a flight into Klamath Falls Municipal Airport for Sunday. He was not successful but he was able to book one for the following day.

Before he fell asleep that night, Frank Eberlein sat on his cot and looked over at his son lying in another cot in a dark corner at Park Headquarters. Eventually he laid down and tried to sleep, but when he closed his eyes, he did not replay images of an enjoyable afternoon fishing with his friend, Al Jones. Whatever went through his mind was not the stuff of pleasant dreams.

Sunday July 20, 1952

The sun appeared bright orange above the east rim of Crater Lake, bathing the wall on the opposite side in a velvety light that fell like a glowing curtain until it reached the lake, illuminating the shallows. Inside the park, it was fifty-two degrees at six a.m. Another beautiful day was forecast. The morning sun helped the searchers warm up as they re-worked the same section of forest they had walked through on Saturday—making certain they hadn’t missed anything in the excitement and half-light the previous evening. When searchers found no evidence of Jones or Culhane by going over the same ground as the previous evening, they enlarged the area south to the boundary and west in the direction of the Park Headquarters.

After a short and not particularly restful night, Frank and his son drove to the overlook first thing on Sunday morning. Alan is the only person alive who remembers the search that day. He described it once in a paper.

The woods search, comprised of a 12 man trail crew, was spaced 20 feet apart combing the area.

Alan Eberlein

The Crater Lake Murders of July, 1952

In order to keep the ground search organized and know roughly where on the map they were walking, crews used compass directions as a point of reference. They walked, as much as possible, north to south between the highway and Powerline Road then reversed course when they reached the area of the road.

Despite searching all day and evening, by Sunday night the dozen men found no sign of the missing executives; neither did they reach the more distant stand of larger trees by the powerlines.

The rangers who spent the night in Annie Creek Canyon resumed searching the pinched river bottom early Sunday. Unlike the woods above them, this was a limited space, less than a football field wide. Snowbanks in the shady canyon were deep enough that July to have hidden a body. Their surface was flat but dirty with a coating of ash and pine needles raining down from the cliff face. A two-hundred-pound object falling several hundred feet would have created an obvious disturbance. Nothing did. Neither had the men fallen into the creek or willows.

Once Packard and his partner determined that no one had fallen into Annie Creek Canyon, this information was passed back to Hallock who notified Oregon State Police. It was eleven a.m. that Sunday.

(l to r) Frank Eberlein, Chief Ranger Louis Hallock, and United Motor Service Representative Ira Kennedy

Courtesy: Klamath Falls Herald and News

There was one other dangerous search performed that day. Immediately west of the overlook is a steep, slippery slope—just above the south canyon wall. The search was undertaken for thoroughness, but with limited expectations. It was difficult and dangerous. The steep sandy edge curved sharply to a freefall more than twenty stories high. After returning to the rim that afternoon from the canyon bottom, Ranger Packard was asked to search this slope. He roped up one more time. Results were the same. The two executives were not there either.

The person most perplexed by the events of the last two days was Frank Eberlein. He’d known Jones for fifteen years. They had fished the local waters together. Eberlein knew his friend was an experienced outdoorsman and comfortable in the woods. It did not make sense that he would venture into this easy-to-navigate little forest with his boss and get them both lost.

The events of Saturday and Sunday did not become public until Monday when the Klamath Falls Herald and News printed the first story about it. It was written by Wallace Myers who stayed with the story thereafter. His account related the confusion and wonder, particularly in a quote from Chief Ranger Lou Hallock.

“This is the darndest thing I have ever run into. The two men just don’t seem to be in the park at all. At least, not anywhere near where they parked that car.”

If there was any silver lining on Sunday, it was that the men had not fallen into the canyon, which had seemed possible the day before. And they were not wandering around in the woods—not within earshot. There was a third theory gaining traction among the searchers. Hallock, Eberlein, and the other organizers had the same idea. Did the missing men meet with some criminal element? The fact that Jones and Culhane had not fallen into the canyon made this third theory more likely. In a way, it was even more worrisome.

After Sunday dinner at Crater Lake Lodge, guests wandered outside to the enclosed patio. From a table there, at the edge of the crater, they could see its full circumference: the sublime spectacle that greets tourists almost every day during the high season. It was uncommonly mild that evening—even warm. Like the day before, the sun set around nine. In the waning light, two objects appeared above the rim, at first indistinct then brighter. Against the moonless night sky, Jupiter and Saturn hung like Christmas lights, and reflected calmly in the laketop.

Five miles from the contented lodge guests, a dozen searchers in the middle of the woods decided to quit. Beside the Powerline Road, the searchers’ flashlight beams became a little cluster darting between the trees. There was yelling as the men huddled up. All were quickly accounted for, a dozen or so. The group turned their backs to the road and headed to the highway where the other searchers and organizers were waiting. The little nucleus of light marking the march back quickly disappeared.

Near enough to have been touched by the distant beams, an unusually proportioned fir tree stood just up Powerline Road. The trunk was split five feet off the ground, creating two trees, slightly off-center, almost parallel.

Below the split, deep shadows covered the forest floor and everything on it. Invisible at this hour were the bodies of two men lying at a right angle to each other just a few feet apart. The record shows that they would not be discovered for some time yet–certainly not in the inky blackness of a moonless night. The only intrusion to the senses was the distant hum of cars on the highway and a gentle wind in the trees. From the shadows, an inaudible question hung in the breeze. How did these men come to be here and why?

🔎 Want more?

The Crater Lake Murders is available now from Genius Books.

👉 Click here to get your copy

Perfect for fans of historical investigations, cold cases, and meticulous narrative nonfiction.