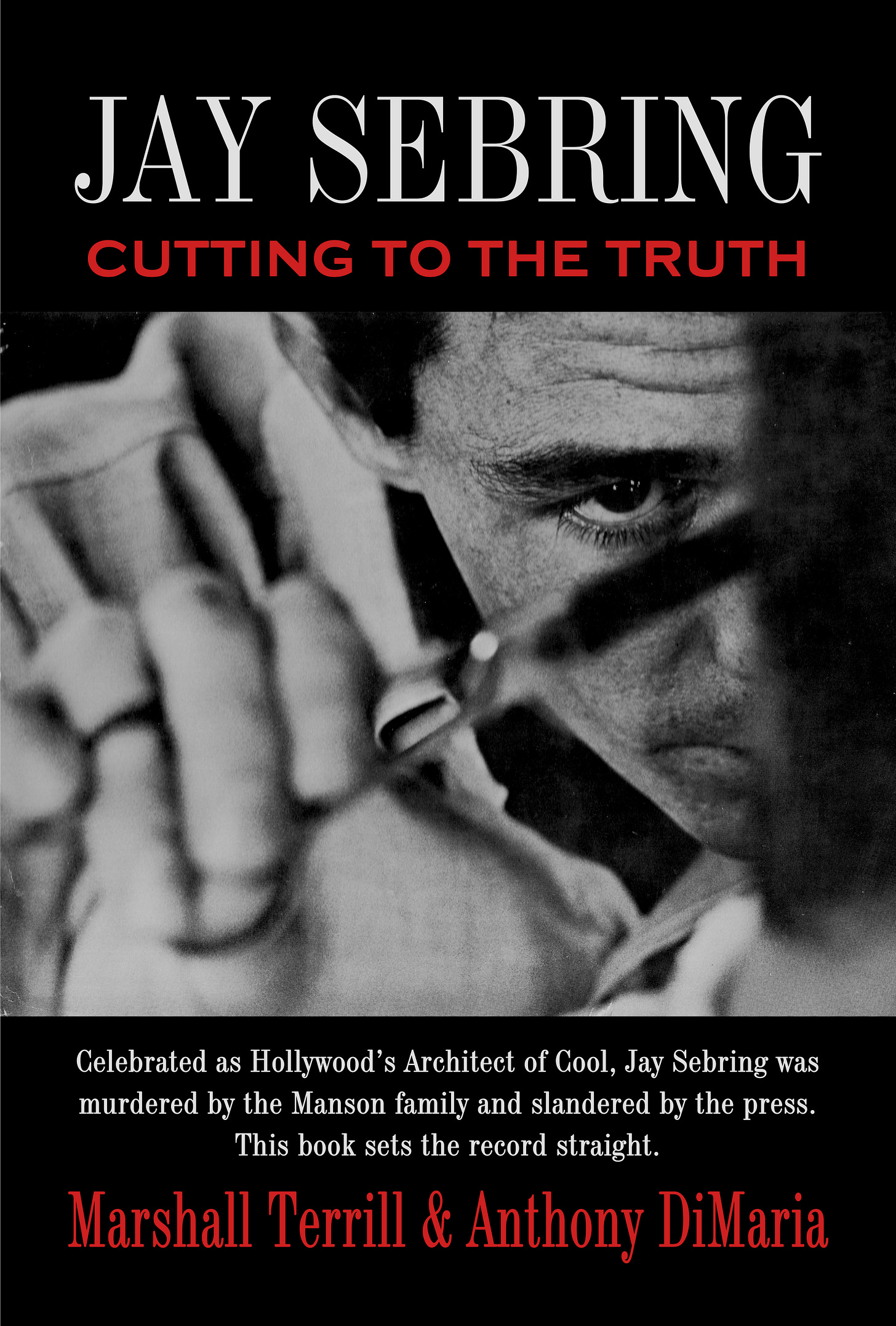

In the glitz and glamour of 1960s Hollywood, Jay Sebring stood as an icon of innovation and style. A visionary who invented men's hair care and design concepts, Sebring wasn’t just a hairstylist—he was the architect of a $100-billion-a-year industry. His revolutionary techniques and signature charm drew legends like Frank Sinatra, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman to his chair, making him a trusted confidant to Hollywood’s elite. From inauspicious roots in Michigan to Hollywood's "star among the stars," Jay Sebring embodied the American Dream.

Yet, in a cruel twist of fate, his extraordinary legacy was overshadowed by the horrifying Manson Family murders. Instead of being remembered for his groundbreaking work and larger-than-life personality, the media painted Sebring as a symbol of Hollywood’s so-called decadence—a distortion that served salacious narratives and tarnished his name.

Jay Sebring….Cutting to the Truth, now illuminated through exclusive insights from Sebring’s family, collaborators, legal and forensic authorities, and criminal perpetrators, reveals the man behind the myth. Discover how Jay Sebring’s influence lives on, shaping our culture in ways we often take for granted. It’s time to reclaim his legacy from the shadows of his tragic end and celebrate the dazzling contributions that made him a Hollywood pioneer and historical figure.

CHAPTER 1

TOM FROM MICHIGAN

Jay Sebring was not born Jay Sebring. He was born Thomas John Kummer. Jay was much bigger than Tom. He had to be created, not born. Stars are like that.

Just as Cherilyn Sarkisian, Stefani Germanotta, and John Joseph Nicholson are different people from Cher, Lady Gaga, and Jack Nicholson respectively, Tom Kummer had to reinvent himself to get where he wanted to be.

Whether it’s being deemed a star among stars, dating Hollywood’s most beautiful women, driving high-end sports cars like Jaguars and Cobras, flying across the globe in private jets, or living in historic Benedict Canyon chalets, this lifestyle is not available to the average person. It is in another atmosphere altogether. You need to escape gravity to get there.

Tom Kummer wasn’t going to be able to do that.

But Jay Sebring could. And did.

This is his story, presented in its entirety for the very first time.

It begins with fire and ice—his mother and father.

Jay’s father, Bernard, was born in Michigan, the son of German immigrant, Kurt Frederick Kummer, and his wife, Ottilia “Tillie” Marie Burk.

Kurt Kummer abandoned his family when Bernard was three, so Tillie took her two sons with her to live with her parents. She earned a living hand-painting porcelain and teaching the same. Her mentor and uncle, master painter George Leykauf, said she could put the breeze in flowers on a tureen. Leykauf porcelain is highly valued today.

She might have passed her artistic abilities on to her oldest son, but Bernard felt he had to become the man of the house during harsh, difficult times. He had to step up and help his mother provide for their family, according to Jay’s sister, Peggy DiMaria. She said of her father:

He needed to have this strength and always be determined and always think outside of himself and what is good for the family and what needs to be done. He worked during the day and went to school at night. There was no childhood in between. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to take chances. He wasn’t allowed.

Bernard and his brother were Jesuit educated in grade school, high school, and college. Bernard graduated from the University of Detroit. His upbringing, moral code, and thinking revolved around regimentation. Restrict yourself. Tell the truth. Always do the right thing. After graduation, he worked for Deloitte and Touche, one of the Big Four accounting firms in the United States.

Jay’s mother, Margarette (“Peg”), was the sixth of eleven children of Scottish immigrant Thomas Wilson Gibb, and Lavona McLain, an Alabama native.

Raised in Pratt City, Alabama, a small town outside Birmingham, she was a coal miner’s daughter from a large family.

“Raising eleven children in Alabama, I would have to conclude they were poor,” said Fred Kummer, Jay’s younger brother. “I think they had a pretty tough time with it.”

One of Peg’s sisters once confided to their mother that classmates made fun of her and she was ashamed of being poor.

“You should never be ashamed of being poor,” Lavona said. “You should only be ashamed of being dirty.” Though often poverty stricken, the Gibb family was wealthy with pride.

Peg strongly believed these two things: soap doesn’t cost much, and it doesn’t cost anything to keep yourself clean. The youngest children in the family only had shoes when they were old enough to go to school, where shoes were required. The shoes were passed down from the older siblings, holes patched with cardboard.

Her father, a small, slight man, worked in the mines. After years down in the pit he developed black lung. Unable to go underground anymore, he turned a room in their house into a barber shop. He set up a chair, saw clients, and made a living cutting hair.

When one of her sisters, Beth, moved to New Orleans, Peg soon followed, working as a switchboard operator.

As a junior accountant, Bernard was often on the road tending to clients. (He later earned his CPA through night school.) On a trip to Louisiana, he met his future wife.

“My parents met in New Orleans,” Peggy DiMaria said. “My dad was there on business and my mother was visiting her sister. It was Mardi Gras. They went out a lot.”

With its distinct blend of French, Spanish, Creole, and American architecture, festive spirit, music-filled culture, bustling nightlife, and relaxed adherence to Prohibition restrictions, the iconic city at the foot of the Mississippi River was catnip for lovers.

It’s unclear how long the two dated or where they spent most of their time courting, but on August 14, 1932, Bernard and Peg were married. Bernard relocated to Memphis, regularly commuting to Pratt City to spend time with his newlywed.

In no time, Thomas, their first child (later known to the world as Jay Sebring), was born on October 10, 1933, in Fairfield, Alabama, at Lloyd Nolan Hospital. Thomas was close with his parents, although he talked to them differently. Everyone did.

Having been raised in a single-parent household with the strains of the Depression indelibly etched in his psyche, Bernard was strict, accurate, regimented, and blunt. He was a no-nonsense, old-school parent, and there was no room for debate or thinking outside the box, especially when it came to his children. Peggy DiMaria said her father had a sharp tongue and equally sharp mind:

He could shoot you down with the English language and really put you in your place when you thought you had it all figured out. He would always come from a different angle than what you were discussing when you wanted to do something or when you wanted to get your way.

In Bernard’s worldview, ambiguity did not exist. You did not go out on a school night. You did not come home after curfew. You did not do a shoddy job on a chore. And you did not dare to ask for an exemption to any of the above. If you did, you knew what the answer was going to be.

Often, Thomas did know what the answer was going to be, but he poked the bear as often as he could, according to his brother.

“I think their personalities conflicted in a very big way,” Fred Kummer said. “Tom pretty much wanted to do what he wanted to do, and Dad was an authoritarian. And the two mixed like oil and water.”

Peg was a listener. When her children came home from school, she wanted to hear all their stories about what happened that day. She had a way of being encouraging, of making the kids feel good about their ideas. She wanted them to have ideas.

“It doesn’t matter to me what you decide to be,” she told them. “What I would like to know is that you be the best you can be at whatever you choose to be.”

It was a far cry from Bernard’s mantra of “Be the best you can be every minute of your life.” Her youngest son Fred Kummer called her the “heart of the family.”

There would be four children: After Thomas (“Tom”) came Geraldine (“Gerry”), then Frederic (“Fred”), and finally Margaret (“Peggy”). Tom was the rugged individualist. Peggy was like Tom, but quieter. Fred and Gerry were well-behaved.

Life in the Kummer household was strict, but certainly not by the standards of the time. If you were supposed to do something and didn’t do it, you were in trouble.

One day Tom was in trouble (again). He hadn’t waxed the stairs properly or had to be told to clean out the fireplace. Punishment was painting the metal fence in the backyard. Bernard was gone for the day; he went into the office a lot on Saturdays, especially during tax season. Before he left, he gave detailed instructions on how he wanted the fence painted.

Peg glanced out the window. Tom was not painting. He was sitting on a rock. The next time she looked out, she couldn’t see him. She grew concerned. Six, six-thirty that night Bernard was going to be home. He was going to want dinner and a fully painted fence when he got there. He could be a little stricter than he needed to be, in her mind, and she gave the kids a little more leverage, but it was all good in the end to her.

She went outside. Tom was sitting on a step directing a group of his friends as they painted the fence.

“Your father’s going to be home soon,” Peg told Tom, her tone hinting that he might be in further trouble if the chore wasn’t finished at day’s end.

He looked up and smiled without saying a word.

The fence got painted. Saint Benedict classmate Jerry Mullin recalls that memorable spring Saturday afternoon.

“I was one of the four guys painting the fence,” Mullin said. “Some people did ceilings, you know, Michelangelo and so forth. I did the fence. Tom was behind the whole thing directing us.”

“He was the leader of the pack,” Peggy said. “He was the one with the idea and he was the one who got everything going.”

Their house had a screened-in back porch. Jay told his parents he wanted to spend the summer sleeping out there because he liked the fresh air and wanted a change of pace. What he did not tell them was that sneaking out of the house at night from the back porch was easier. He would head to his buddies’ houses in the middle of the night.

Tom was usually awake most nights. Like many artists, he was a nocturnal creature.

“He was at his best at night,” his sister Peggy said. “It was like he didn’t want to lose the time when you normally sleep. He would want to spend that living life as well.”

Childhood chum Jim Graham described Jay’s adventurous spirit as a young lad:

I heard a stone at my window. And it was Tom. I went downstairs. My parents were sleeping, and he said, “C’mon let’s go down the street go out and do something.” I said, “Tom, man, it’s the middle of the night!’” I wasn’t gonna go out there.

Jim complained the stone might wake his parents to which Tom suggested, “If you tie a string to your foot or hand then put it out the window, I can just pull on it.” Tom was a mischievous guy and marched to a different beat.

The problem was as much as Tom loved the night, he hated mornings—a trait that lasted well into adulthood. His sleeping patterns resulted in frequent exchanges between Tom and his father.

In the 1940s, Detroit was hardly a sleepy town but a bustling company city that “put the world on wheels.” Grand Boulevard was plastered with ads for Ford, Cadillac, and Firestone. J.L. Hudson’s was the big department store downtown. The last of the passenger steamers cruised Lake Erie and two giant ferries took passengers across the river to the amusement park on Boblo Island.

The Tigers played at Briggs Stadium. For coffee, Qwikee Donut and Coffee Shop had three downtown locations. This was the city’s golden era. The population peaked in 1950 at just under 1.9 million people.

It is true auto workers were the highest paid manufacturing employees in the country, but what’s less well known is that it wasn’t steady work because of material shortages after World War II. It was unhealthy work, too. The plants were filthy, with bad air quality and oil swirling all around. Men contracted black lung disease, cancer, and a variety of musculoskeletal disorders in these plants, not to mention punctures, cuts, burns, electrocution, and other non-fatal injuries that amputated various body parts. “Horror stories,” one Detroiter of the period called them.

After the war, many smaller auto companies went bust. Most auto workers had side jobs. Civic leaders were dismayed that after the war all the people who had flocked there for jobs didn’t return home. Housing was scarce. Highland Park, where the Kummers lived, was a working-class neighborhood at the time. The Ford Highland Park plant employed thousands of people.

Even still, kids in Tom’s neighborhood had idyllic childhoods. They walked everywhere because few people had cars. They knew everyone and who lived in every house. In winter they ice skated on Ford Field and sledded off the roof of Tom’s garage. In summer they rented ponies at Palmer Park and played pickup games of baseball and basketball. Tom directed his friends in skits they put on in the garage, with singing, dancing, and comedic bits.

“He was very friendly, and he had a charisma,” said Jim Graham, who first met Jay in grade school at Saint Benedict’s and knew him into adulthood. “He was always upbeat, but I could see where people might have thought he was a little introspective.”

That introspection was most likely inherent. After all, he came from a lineage of creative individuals.

At his grandmother Tillie’s house, Tom was exposed to jars of porcelain paint, the tang of turpentine, and the glow of creation. George Leykauf had Tillie paint the gold leaf scrolling on the rims of dishes and platters. He only wanted the real thing. He believed raised paste ornamentation detracted from the artistry of the pieces. Leykauf’s work is noted for never repeating a theme. Tillie explained this to Jay. He was exposed to exacting standards of artistry, beauty, and quality at a young age, the very qualities he would incorporate into his salons decades later.

Tom was not a particularly dedicated student. He wasn’t a wise guy, creating problems in class. He just wasn’t present mentally. He drew—cars, ships, movie stars, pinup girls—and dreamed. Big. For grade school he went to Saint Benedict’s, a Catholic school. His mother was called in to speak with Tom’s teacher because he spent his time in the classroom staring out the window with a smile on his face, oblivious to what was being taught. Peg knew Tom was wired differently than the other children.

“You know, once they lost him, they lost him, and they probably lost him as soon as they started talking, quite honestly,” his sister said.

Perhaps, if Saint Benedict’s had had an art program or a subject that remotely appealed to Tom, they might not have lost him. Schools didn’t have anything like music or art programs back then. Public schools had shop classes, but they didn’t have arts programs.

Once he sat behind Jerry Mullin at a schoolyard lunch table, intensely drawing on the inside fold of his beige raincoat collar. “Whatever you do, don’t put your collar up,” Tom said when he was done. When they went to chapel, Tom’s buddy flipped his collar up, only to have it seized by an angry nun who hauled the boy outside. Tom had drawn a naked woman. In ballpoint ink.

Tom was a creative powerhouse. He just knew what looked good.

Very Best Candies on Hamilton Avenue in Highland Park had window waxing contests every year at Halloween and Tom won the competition twice.

From time to time, Peggy would do their mother’s hair, and Tom would walk in the kitchen, watch for a moment, and then make suggestions.

“You could try this,” he would say. “Or you could do it like that, that way.”

His friends remember him as being a fastidious dresser whose shoes gleamed. Sartorially he was put together, even in eighth grade.

“He was very good looking and presented himself nicely,” Jim Graham said. “And that really worked well in his business obviously, styling.”

After he graduated from St. Benedict’s, Tom attended the University of Detroit Jesuit High School. A Jesuit education is strict and academically and intellectually rigorous. In other words, a disaster for Tom. He was kicked out after his freshman year for bad grades. In his yearbook, he appears in his class photo, kneeling and squinting into the sun, but that’s his only appearance. No glee club, camera club, science club, or sports teams. His report card for June 1949 stated the reason for withdrawal in one word: “Failure.”

Tom’s extracurricular activities as a teenager included joyriding with his friend Jerry Johnson. The two often ventured to a used car lot on Woodward Street—Detroit’s Main Street. The dealer made the mistake of leaving the keys in the cars, and they would “borrow” a car, drive it around all weekend, and bring it back on Sunday night.

The older Tom got, the more tensions rose in the Kummer home in classic father-son clashes.

“It’s the little things that count,” Bernard told Tom. “Be on time or earlier. Do what you say, no matter what. I’d like to compliment you some time and not always correct you.” (It was more than a little ironic since Bernard also liked to stay up at night. “He was the only CPA that I ever knew of that went to work at 10:00 a.m.,” his daughter said.)

A letter Tom wrote to his father in 1949, a year before he left home, revealed the general shape of what was an ongoing conflict.

“Instead of being smart and snippy when you speak to me, I should take the right attitude and not scowl and make smart remarks,” Tom wrote in what strongly smacks of a mandated apology letter. “When I have done something wrong, I should not only say, ‘I’m sorry’ but I should also prove myself.”

A pillar in the Catholic community, Bernard lobbied to enroll his expelled son into Catholic Central, a parochial all boys school—and Tom was admitted. Bernard had high hopes but should have known better. It wasn’t as strict but his grades were still not up to par and Tom didn’t last long—about a month, with Tom doodling, staring out the window and flunking a majority of his classes.

Months after Tom started at Catholic Central, Peg and Bernard received a phone call. The United States Navy was on the line. On October 10, 1950, Thomas John Kummer personally submitted his enlistment form on his seventeenth birthday to the local naval office. The authorities found the parental consent signature of Bernard John Kummer suspicious. For good reason. The teen had forged his father’s signature in the absence of both parents. As Tom happily waited to be recruited in the armed forces, his plot was foiled when naval officers notified the Kummers.

Bernard was shocked. They sat down after dinner—the time reserved for anything serious in the Kummer home—and there was a long conversation.

“I want to see the world,” Tom said, pleading his case. “I need to see the world.”

They contemplated his words. Maybe this is what Tom needs, they thought. Maybe he should go in the service. It might be good for him. School certainly wasn’t. After much contemplation, Bernard reluctantly signed.

“He [Tom] was probably thinking, I’m out!” Peggy said. “I’m out of the house. No more rules, no more school. And of course, what he found out was that the navy was a whole lot of rules.”

Tom was about to discover his father’s regimentation paled in comparison to life in the American military. Living under Bernard Kummer’s roof was a frolic contrasted with a regiment of commanding officers and serving on a destroyer during war time.

In time, he would understand this.

Ready to finish reading? Find the book here: Jay Sebring