First Chapter: The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes And His Contemporaries

by Michael Cohen

In 1891, a new London magazine, The Strand, decided to publish short mysteries in connected series. Arthur Conan Doyle’s short stories about Sherlock Holmes nearly doubled the magazine’s circulation, and Doyle became rich. Other magazines searched for tales with the same kind of appeal. Dozens of men and women began to write detective stories in the serial format of the Holmes’ Adventures.

An enormous flowering of this kind of tale followed, with stories that featured women and men detectives, professionals and amateurs, young and old, aristocrats, gentlefolk, and plain folk. Detectives went rogue and became burglars and conmen. Others developed occult powers. It was a Golden Era of detective fiction, and it lasted for two and a half decades until the First World War. Nothing of its variety had been seen before.

Michael Cohen’s The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes and His Contemporaries is a guide to this trove of stories that fascinated readers a century and a quarter ago. In clear and crisp prose, Cohen takes you through the variety of stories with brief descriptions, and he shows you where to find the stories online in their original, illustrated magazine versions. Here you’ll find names you might know, such as Chesterton’s Father Brown, and less well-known ones, such as Ernest Bramah’s blind detective Max Carrados, Anna Katherine Green’s debutante detective Violet Strange, and Gelett Burgess’s “Seer of Secrets,” Astro.

1. How He Did It: Sherlock

Sherlock Holmes and The Strand Magazine

Arthur Conan Doyle’s success was only partly owing to his writing skills. He had nothing to do with the bulge in literacy rates created by parliamentary acts of ten and twenty years earlier. Nor did he participate in editorial decisions George Newnes and Herbert Greenough Smith made to eliminate serialized novels in The Strand Magazine and to concentrate on short stories with continuing characters, though Doyle seems to take some credit for those decisions in his autobiography.

Regardless, Doyle was a storyteller of considerable talent, and his talent was at its most concentrated pitch when he wrote about Sherlock Holmes. Looking back at the heyday of Sherlock Holmes’s popularity, the editor of The Strand Magazine, who had called Doyle the greatest short story writer since Poe, reflected on what made the stories a success. He decided it was “the ingenuity of the plot, the limpid clearness of the style, the perfect art of telling a story (Pound 41). Greenough Smith’s desiderata will be useful in comparisons with other writers going forward; let us see how they are on display in the first group of stories that began a Golden Age of detective fiction.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

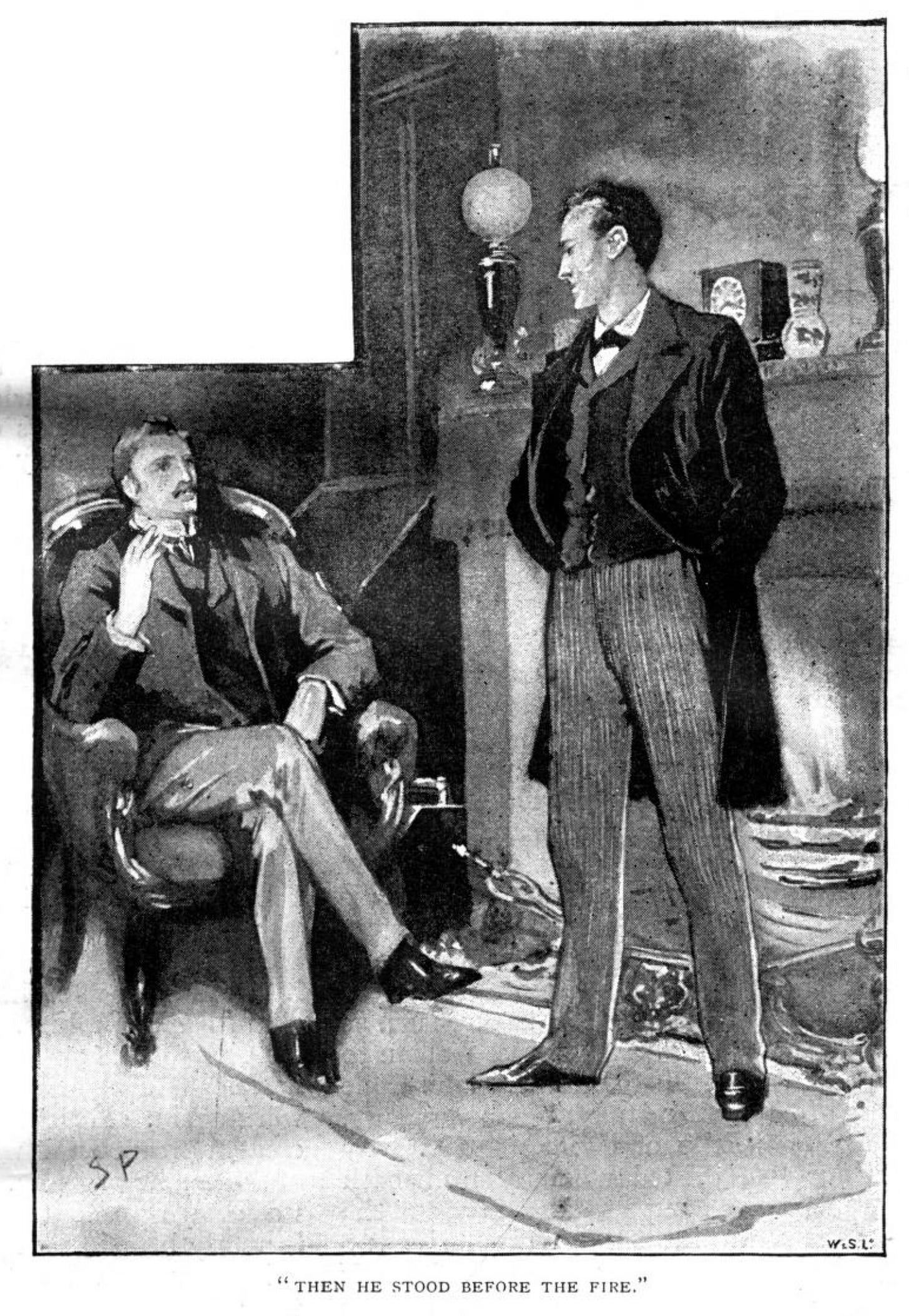

In my unfocused memory of The Adventures, when I have not reread them for a while, each story begins while Holmes and Watson sit on either side of the fire in their Baker Street rooms, while outside the equinoctial gales of September or March blow, or the fogs of November swirl around the windows. Never mind that Watson has married and moved out of Baker Street in a novel published before the first of the Adventures, and that three of them begin at Watson’s house. Never mind that it is full spring or summer or midwinter in several stories.

But there is some truth in this impression of the typical Holmes story, with the two men comfortable in their bachelor lodgings, surrounded by the homey and the familiar furnishings of their bourgeois—tempered with the Bohemian—life. The Adventures depict a world with Holmes and Watson at the still center, while outside are concentric zones of danger and discomfort. Immediately outside is the city, with its millions of nameless and faceless inhabitants, the product of an enormous population migration from the country into the metropolis over the previous century. In this mass of people, true anonymity is now possible in a way it was never before in a country of small rural settlements and modest-sized towns and cities. This is Baudelaire’s urban amusement park, the ever-changing prospect for the flâneur who roams the avenues and alleyways, but it is also the ground for Poe’s “Man of the Crowd,” who is “the type and the genius of deep crime,” precisely because he cannot be identified, separated, from the mass; “he refuses to be alone,” in the deep heart of the city; he is the book that will not allow itself to be read.

Given the anonymity of the mass of people gathered in the city, and the potential danger that namelessness represents, it is not surprising that one of Holmes’s characteristic weapons is his ability to place someone he observes. Your anonymity disappears as Holmes sees that you are a doctor who has recently been in Afghanistan, a typist, or a retired sergeant of marines, left-handed, having just come from the Wigmore Street Post Office, with careless servants and no gas laid on at your house. Holmes nullifies the anonymity of the metropolis so that we become known. He negates the possibility of hiding amongst the unknown masses, as if we were living in a village.

Not that the real villages are safe places. Beyond the first dark circle of the city that surrounds the bright, warm enclave of 221b Baker Street lies an even darker circle of countryside, where the helpless lack any recourse to constable or passerby. Thus Holmes corrects Watson’s naive pleasure in the peaceful rural scene as they are training through it: “It is my belief, Watson, founded upon my experience, that the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.” Four of the Adventures deal with crime in the country.

Finally, out beyond the city and the countryside, out beyond England, is a circle of not just occasional crime but of lawlessness and vigilantism. In America, in Australia, on the open ocean, and in the far reaches of the empire such as India and the Andaman Islands, the order of civilized Victorian life is trumped again and again by the corruption of colonialism, by the savagery of the response to its savagery, by the struggle between the powerless and the powerful, and by violence arising from slavery or in penal colonies, prisons, and prison ships. And more and more often, the violent aspects of the empire come home to roost in London.

But what constitutes disorder is not always what we think of as crime. The social order can be disrupted by a violation of class behavior, of gender “rules,” or of failing to observe presumed differences between the races. Disorder for one person may consist for another as merely asserting her identity as a person.

“A Scandal in Bohemia” begins with Dr. Watson returning to Holmes’s rooms in Baker Street on a whim, a desire to see his old friend again. Readers must be reminded—if they’ve read A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four—or informed, that Watson no longer lives there, but has married and resumed his medical practice. The background takes several pages. Contrast this with the opening of the second story, “The Red-Headed League,” and we can see the extreme economy of exposition Doyle is capable of:

I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman with fiery red hair.

Not bothering to explain the reason for this visit, Doyle devotes half a sentence to the setup before he shifts to a description of the red-headed man who has been the subject of an elaborate plot to get him out of his shop (a so-called red-headed league to pay men with red hair a comfortable sum from an inheritance for doing nominal work) so that a notorious criminal named John Clay can tunnel from under the shop to the bank vault next door.

To return to “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the first story does not actually begin with the current Holmes-Watson relation; it begins, and ends, with the statement that for Holmes, Irene Adler will always be the woman. To get to the significance of this, we must wait for the plot to unfold, beginning with the King of Bohemia, who has dropped Irene Adler and wishes to marry a princess, telling Holmes that Adler has compromising letters of his, which are authenticated by a photograph of the two of them together. The plot driver of the compromising letter or letters or photograph is not uncommon in detective fiction of this period and earlier. The subject of Poe’s second Dupin story is a compromising letter, a hiding place not immediately obvious but made obvious by the detective (here Holmes forces Irene Adler to show it him by a ruse of fire), and a monarch who sends an agent, while the monarch here comes himself because to trust a delegate would put the king in his power. Doyle uses the compromising letter plot at least twice more in his short stories, in the adventures of “Charles Augustus Milverton” and “The Second Stain.”

The gender issue raised by the first line of the story indicates how pointedly gender as a construct is foregrounded at the very beginning of the Holmes short stories. In this story it is tied up with another frequent aspect of detective fiction of the nineteenth century, namely disguise. Disguise here shows up in the person of the king, who unsuccessfully disguises himself from Holmes’s penetration. Then Holmes himself demonstrates his mastery of disguise, first as a “drunken-looking groom, ill-kempt and side-whiskered, with an inflamed face and disreputable clothes,” and then again as “an amiable and simple-minded Nonconformist clergyman.” The compactness and specificity of these descriptions show distinguishing features of Doyle’s style. In Fiction, Crime, and Empire, Jon Thompson calls it “a realistic style notable for its vivid, precise detail,” and says it makes the stories eminently accessible to readers of “a new, quintessentially popular genre” (Thompson 61). The lucidity of Doyle’s style is especially apparent after the passage of more than a century and a quarter. Ordinary readers writing reviews of late Victorian fiction on library apps such as Goodreads and LibraryThing frequently complain about difficulties of style and vocabulary. Practically no such complaints can be found in hundreds of current readers’ reviews of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes.

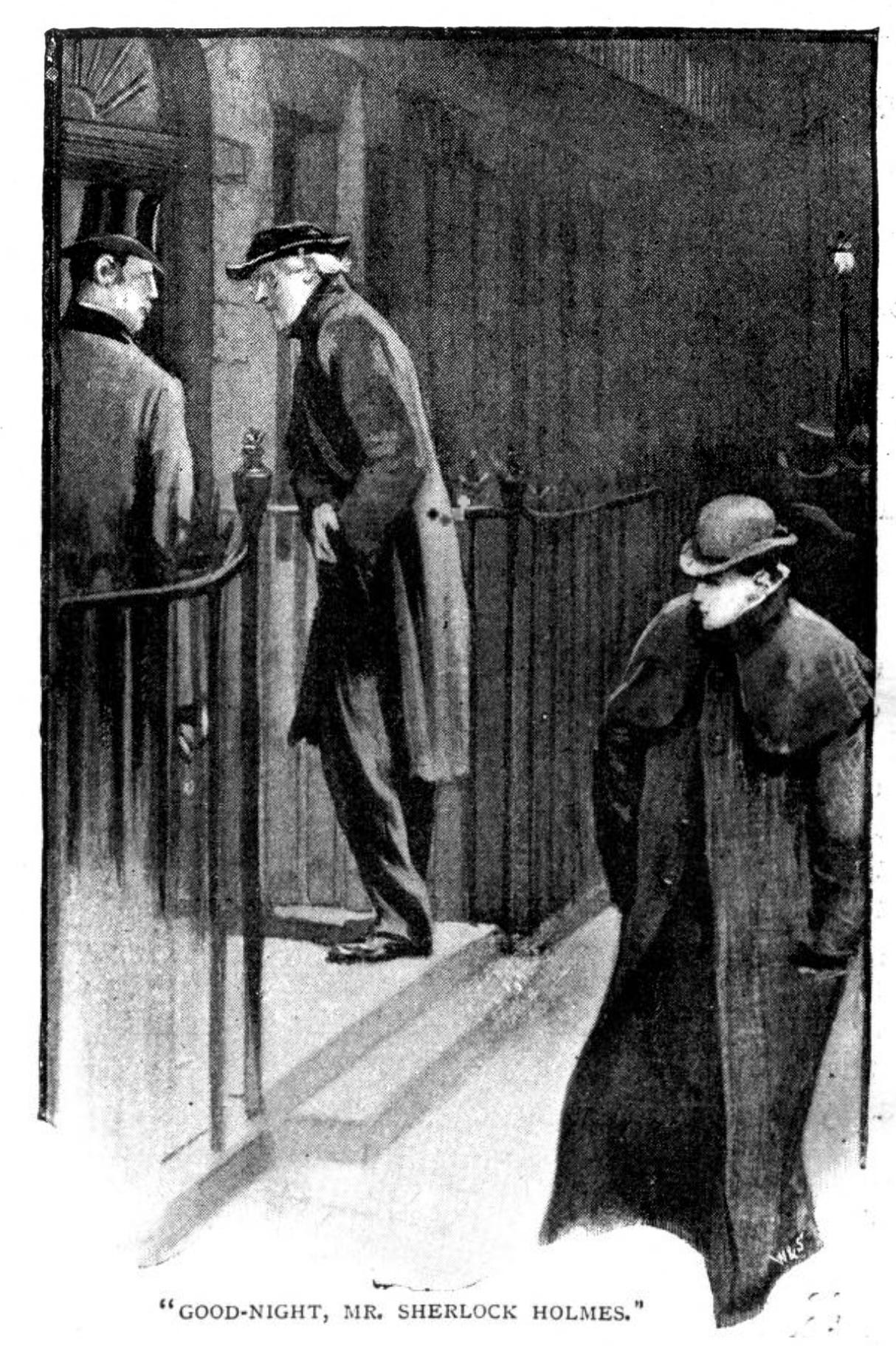

Both of Holmes’s disguises take Irene Adler in, but she has the last laugh. Holmes gets into her house (as the clergyman, pretending to be injured), and Watson throws a smoke bomb while raising the cry of fire. Holmes sees where Adler rushes to: a secret compartment in the wall where she keeps the photograph. But Adler realizes a trick has been played, and who has played it. Disguising herself as “a slim youth in an ulster,” she follows him back to Baker Street, and before disappearing, she wishes him “Good night, Mister Sherlock Holmes.” Joseph Kestner, in Sherlock’s Sisters, calls Adler’s disguise a “transgression of gendered borders” (2003 Kestner 87). The photograph is gone when Holmes and the king go looking for it the next day, but a note from Adler says she will not use it to spoil the king’s marriage, but will keep it to safeguard herself from him, one who “has cruelly wronged” her. Adler is the woman who out-thinks, out-disguises, and out-moralizes a man, and that man is Sherlock Holmes. ”She has the face of the most beautiful of women, and the mind of the most resolute of men,” says the king, who doesn’t get it that he’s been outclassed, even though Holmes makes a point of it. When the king says what a queen she would have made and what a pity it is “that she is not on my level,” Holmes replies, “she seems indeed to be on a very different level to your Majesty.”

In his very first Holmes short story, Doyle lets his detective fail, has the failure come at the hands of a woman, and shows Holmes unimpressed by, and even slightly disdainful of, royalty. Doyle takes an ordinary incriminating letters situation and treats it with freshness, drama, irony, and humor. First a huge, six-foot, six-inch, outlandishly dressed and masked figure who turns out to be the King of Bohemia enters and tells his story. Holmes tells him he’ll have to wait, since the detective has “one or two matters of importance to look into just at present.” Then Holmes gets into elaborate disguise, twice, to investigate Irene Adler, and what is the result? In the first disguise he is “half-dragged” into becoming a witness at Adler’s wedding ceremony. In his second disguise, his discovery of Adler’s hiding-place for the photograph is seen by her as a trick, and she immediately dresses as a boy, follows him, and confirms her guess that it is he. Holmes does not see through her disguise, misses his chance to recover the photograph, and has to settle for a photo of her instead.

The ingenuity in the second story, “The Red-Headed League,” consists in enlivening the rather simple tale of thieves tunneling into a bank basement with the ruse to get the pawnbroker out of his shop, beneath which the tunnel begins, and the ruse is treated comically, in the outlandish scheme and the seriousness with which the pompous pawnbroker takes it. Because he has two stories to tell—the pawnbroker’s of how he is lured out of his shop each day by the promise of £4 a week for copying the Encyclopædia Britannica, and the real adventure of the apprehension of the thieves in the act of entering the bank—Doyle wastes no time, as we have seen, in getting into his tale. The device of a scam to remove the resident from his premises is used twice again by Doyle, in “The Stock-Broker’s Clerk” (Memoirs) and “The Three Garridebs” (Case Book).

No fewer than three of the Adventures, a quarter of the stories, use the plot driver of a greedy older relative who wishes to control the fortune of a daughter or stepdaughter. There is an overlap with the inheritance plot, where a malefactor, wishing to supplant another person as heir, uses murder to effect it. But in two cases here the methods are less drastic. In “A Case of Identity,” Mary Sutherland consults Holmes because her fiancé, Hosmer Angel, seems to have disappeared. Holmes quickly finds that Sutherland’s stepfather, Windibank, has impersonated a suitor (Holmes, his clients, and his opponents all assume disguises) for his stepdaughter, got her to pledge eternal fidelity, then staged a wedding where no groom shows up. As Windibank points out when he is confronted by Holmes with his actions, there is no crime here, though Holmes offers to horsewhip the man in punishment for his cruelty.

He took two swift steps to the whip, but before he could grasp it there was a wild clatter of steps upon the stairs, the heavy hall door banged, and from the window we could see Mr. James Windibank running at the top of his speed down the road.

At the beginning of the story, Sherlock Holmes insists on the bizarreness of the ordinary, and wins his point against Watson’s ill-chosen example from the daily paper. But Holmes makes another point: that it is not the great crimes that have the most interesting and bizarre features, and immediately Mary Sutherland shows up to bear him out. The oppression of the daughter is more ominous in “The Copper Beeches,” where a father imprisons his daughter and hires a look-alike to represent her while the lover observes from outside, the object being to discourage him from his attentions, while the father continues to enjoy the daughter’s income. Doyle might as easily have called the story “The Chestnut Tresses”; it’s a red-headed league story in which the desired modality of the subject is presence rather than absence, and where the hair color, and in this case its length, is just as important. But the lover is not discouraged, sees through the ruse, and the daughter escapes and elopes with him.

The third example of the stepfather’s coveting the stepdaughter’s income turns deadly. In “The Speckled Band,” Helen Stoner tells Holmes of her impending marriage, of Dr. Grimesby Roylott, her violent stepfather, who enjoys income that her twin sister and she would take with them if they marry, of the suspicious death of her sister two weeks before her marriage, and of her fear that she will die the same way. Dr. Doyle has his detective comment that “when a doctor goes wrong, he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge.” Holmes and Watson investigate and encounter a poisonous “swamp adder” that Roylott introduces to the girl’s room via a ventilation grate and a bell-rope. He usually keeps the snake in a safe, calls it back with a low whistle, and feeds it milk. The snake retreats when Holmes lashes at it, and it kills Roylott. “The Speckled Band” seems to have been Doyle’s favorite among all the stories. He never let on that it might have been just a little over the top, but that’s what John A. Hodgson argued in a 1991 essay “The Recoil of ‘The Speckled Band’.” Hodgson thinks Doyle could hardly have been unaware that there is no such snake as a “swamp adder,” that snakes have no external ears and cannot hear low whistles, that they don’t drink milk, can’t climb a rope, and certainly can’t live in an airtight safe. But as Doyle remarks in his autobiography, “I have never been nervous about details” (Memories 156). In any case, as Hodgson notes, such discrepancies do not prevent this story from being a favorite among readers as well as with its author.

Two other stories in The Adventures involve murders, “The Boscombe Valley Mystery” and “The Five Orange Pips.” In the former an English landowner who had been a highwayman in Australia kills his blackmailer, and Holmes saves the blackmailer’s son from a charge of murder; in the latter a former Ku Klux Klan member is killed because the Klan wants incriminating papers he has. The Klan does not know he destroyed the papers, and one of their members returns to kill his innocent brother. Then the nephew is threatened and consults Holmes, who fails to save him from death. Holmes traces the guilty man, but his ship is lost at sea before he can be taken by American authorities.

A fair test of Doyle’s ingenuity is looking at what he can do with the most hackneyed of subjects. Bigamy, since Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret in 1862, was a staple of sensational literature in England. Only one of Doyle’s stories from the nineties deals with it, and that glancingly. Lord St. Simon, whom Doyle describes as having “a pleasant, cultured face… with something perhaps of petulance about the mouth, and with the steady, well-opened eye of a man whose pleasant lot it had ever been to command and to be obeyed,” is at the altar of St. George’s in Hanover Square, about to marry the American Miss Hatty Doran, whose father is “said to be the richest man on the Pacific slope.” Doran sees, standing in the first pew, Frank Moulton, whom she married years ago in the mountains of the American West, before he went off to make his fortune, with a promise to return. She has been convinced that he was killed by Apaches over a year before she met Lord St. Simon. She is stunned, but goes through with the service. Later, during the wedding breakfast, she and Frank slip away. Holmes finds the couple and brings them together with St. Simon to explain.

Though technically it is a bigamy story, and the runaway bride aspect is certainly sensational, Doyle does not highlight the sensationalism. He makes fun of the fuss in the society papers reporting the runaway bride, foregrounding Holmes’s lack of snobbery. He also finds the Americans refreshingly naïve. He brings the couple in to explain themselves to St. Simon and admires their candor. But the first thing that struck me about this story was how little it hangs on—that is, it depends entirely on Hatty Doran’s silence: she does not simply tell her husband or her father what the problem is, at the wedding, in the carriage afterwards, or at the wedding breakfast. That silence seems in turn to be caused by the class problem. Lord St. Simon’s situation is apparently imagined to be too elevated and austere for Hattie to tell him that his expectations of a wife and fortune have suddenly disappeared. But the story as a whole makes a more complex assertion about the class system. Lord St. Simon himself is made into a stuffed shirt. Holmes, as always in these stories, is peculiarly outside the class system and unwilling to genuflect to it: when Lord St. Simon says Holmes probably is not accustomed to handling problems at this level of society, Holmes assures him he is “descending” and that his last client was a king.

The circumstances of the tale are historically accurate: the increasingly impoverished British aristocracy frequently resorted to marriage with rich commoners from the United States to pay the bills and keep from having to sell the country houses. To that extent the story chronicles a real decline in power of class, and here the story has the aristocrat failing in his attempt to marry the heiress. The underwriting of the aristocracy by non-aristocratic, democratic money made by people from a supposedly classless society who suddenly find themselves rich is frequent enough to be remarked on by a society newspaper Watson reads to Holmes at the story’s beginning. But the economic rescue fails to happen here.

Holmes is very assertive about not being impressed by class, and in fact at the end of the story he sits down to dinner with the commoners from America in a dinner party where the aristocratic fifth member declines to participate (“there you ask a little too much,” says the lord) and where Holmes announces that he foresees a new world order where the flags of Britain and America will be quartered and one English-speaking nation will span the Atlantic, not only class boundaries but national ones dissolved as well.

Another hackneyed plot driver in Victorian crime literature is jewel theft. Two stories in The Adventures involve the stealing of jewels, “The Blue Carbuncle” and “The Beryl Coronet.” Each is an original take on the subject.

The young head attendant at the Hotel Cosmopolitan succumbs to the temptation to steal the Countess of Morcar’s famous diamond, the Blue Carbuncle. Tortured by conscience and convinced he will be caught and searched at any moment, he hides the jewel by forcing it down the throat of one of his sister’s geese about to go to market. She has promised him one of the birds, but he fails to see there is another one in the flock identically marked to the one who swallowed the diamond. He takes home the wrong bird. Holmes comes into possession of the bejeweled bird by accident, and traces the selling of the geese back until he finds the hapless thief, whom he lets go. “This fellow will not go wrong again,” Holmes says, “he is too terribly frightened.” The whole story up to that point is treated with humor, as a comedy of mischance.

“The Beryl Coronet” is a darker story. Though the jeweled crown of the title is several times called a “public” treasure, its owner, a duke, pawns it for a loan from a banker named Alexander Holder, who takes it home with him rather than entrust it to his office safe. Holder’s niece has become entangled with a scoundrel of a gambler named Sir George Burnwell. Learning of the coronet, Burnwell convinces the girl to bring it outside to him during the night. Holder’s son hears the girl leave and follows. Burnwell and the son struggle over the coronet, from which a corner containing three jewels breaks off and is carried away by Burnwell. Holder wakes up and finds the son with the coronet in his hand, accuses him of the theft, and calls the police. The son, not wanting to implicate the niece, with whom he is in love, refuses to explain himself. The girl leaves Holder’s home and joins her lover. Holmes discovers what really happened and uses Holder’s money to buy back the coronet piece from the dealer Burnwell sold it to.

Doyle’s toying with names can be amusing: here Alexander Holder is the materialist banker. Shylock can’t be sure about the priorities between his ducats and his daughter, and Holder says “I have lost my honour, my gems, and my son in one night.” Sir George Burnwell (burns money well? burns the candle at both ends?) is the villain. The money lender cringes before the aristocracy; the aristocracy is venal and irresponsible about public treasures; “gentlemen” are allowed to prey upon the innocent. The story is about many of these things, and least about jewel theft. The jewels here are more symbolic, since a coronet is in fact the crest of a duke, and these jewels don’t have the usual portability that makes them so attractive to thieves. Jewels attract thieves because they are condensed money: they get the most value in the smallest space, and jewels attract crime fiction writers because they attract thieves and because of the aesthetic element: the carbuncle is “a brilliantly scintillating blue stone, rather smaller than a bean in size, but of such purity and radiance that it twinkled like an electric point in the dark hollow of his hand.” For Doyle, however, the jewels are only a means to telling a story, usually far from the usual world of jewel thieves.

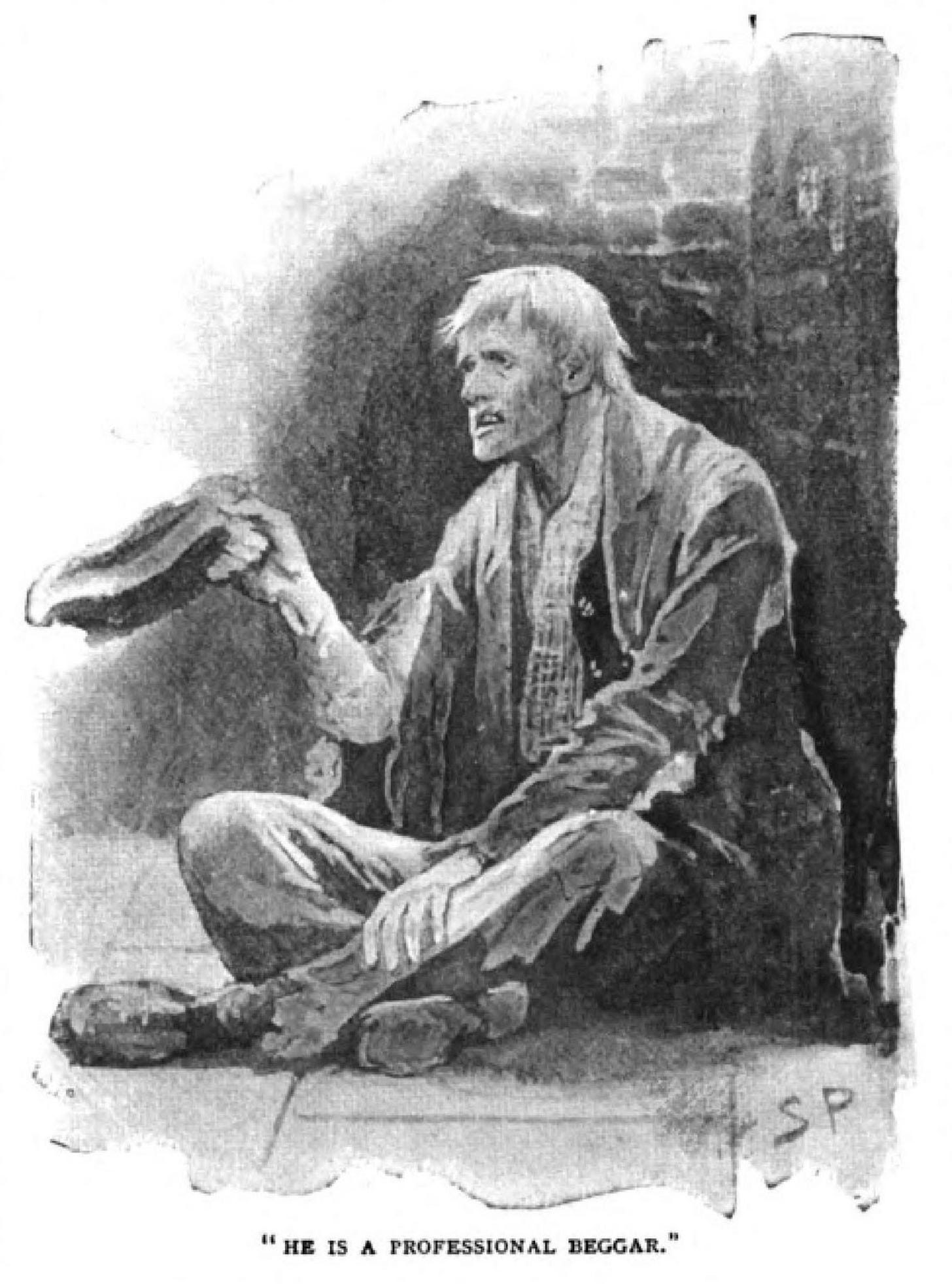

The two remaining stories of The Adventures are at once the most original and the most peculiar of the twelve. “The Man with the Twisted Lip” is the story of Neville St. Clair, who gives up his job as a reporter on a London evening newspaper when he discovers that, with a dirty face and a make-up scar on his lip, he can make as much money in one day of begging on the street as his reporter’s job pays in a week. He begs, he saves, he buys a house in the country, marries, has children—all while commuting each day to the city, not to a respectable job, but to begging. One day his wife is passing the opium den whose proprietor St. Clair pays for a room to change in twice each day. She sees St. Clair at an open window and calls his name, at which he makes a startled noise and disappears from view. She raises a cry, but is prevented from immediately entering by the proprietor. When she does enter, with police, there is no one there but a beggar and an open window onto the river. The beggar is arrested on suspicion of having murdered the gentleman. As he admits to Holmes later, St. Clair would rather have gone to prison or be executed than “have left my miserable secret as a family blot to my children.” “The Man with the Twisted Lip” begins with Watson called out by a distraught wife to bring home her husband from an opium den. Isa Whitney, “a slave to the drug” since college days, has been absent from home for two days. Watson goes straight to the opium den the wife names and finds Whitney there. He also finds Sherlock Holmes, disguised as an old reprobate and opium addict. Watson sends Whitney home in a cab and joins Holmes, who is investigating the St. Clair disappearance for his wife, for this is the very opium den where St. Clair daily adopted his disguise as a beggar, and where he was last seen.

“The Man with the Twisted Lip” is a story that is not about crime but about transgressions worse in the Victorian rule book: the opium addiction with which it begins (and Holmes alludes to his cocaine habit there as well) and the begging that seems to constitute an equally unthinkable sin against respectability. Holmes himself points out his surprising failure to figure this one out immediately; the raffish Holmes who injects cocaine, eats only every other day when he’s working, and rejects the work of the world to create his own profession, has advantages in figuring out such a problem, but the Holmes who is a respectable gentleman may not be able to think outside middle-class lines so easily. Hence the picture of Holmes propped up on pillows, smoking all night—underlining his raffishness—but doing it in his client’s house in his function of a respectable consultant hired by the missing man’s wife. For many critics (for examples, Audrey Jaffe, Stephen Knight 1980, Rosemary Jann, and Clare Clarke 2014), this story blows up complacent notions about how the Holmes stories simply reproduce and reinforce Victorian bourgeois values. It doubly illustrates the ugly underbelly of genteel Victorian life. How can you tell that the respectably dressed gentleman you see on the underground isn’t on his way to a day on the streets as a common beggar? Or perhaps on the way to a 48-hour opium binge in the East End? What Jaffe calls “the indeterminacy of social identity” (418) extends to Holmes (respectable consulting detective or languid, cocaineinjecting æsthete?) and, outside the fictional boundary, to Doyle (hard-working physician or lazy supplier of pap to the hordes of avid sensation-lovers?). The indeterminacy of identity threatens Holmes’s special talent of plucking men and women from the city’s anonymity by discovering their occupations from merely looking at them, Moreover, the story ends with less than real resolution. St. Clair gets to keep his secret by agreeing that the beggar will never be seen again. But what will happen next, we wonder. How will St. Clair support his family’s way of life without a job, or with the prospect of a much lower-paying one?

A very different story, but an original and peculiar one nevertheless, “The Engineer’s Thumb” is more adventure story told to Holmes rather than a problem for him to solve. He does solve one small aspect of it, but still fails to catch the culprits. The hydraulic engineer Victor Hatherley is hired by a German who takes him to a remote village in Berkshire. A little gang of counterfeiters, two Germans and an Englishman, needs someone to fix the hydraulic press they use for coining. They make up a story about using the machine to compress the fuller’s-earth that’s found in the neighborhood. Hatherley sees what’s wrong with the press, but also sees through their story, and is imprudent enough to comment about it. He is locked into the press, which is as big as a small room, and the machinery is started. The black ceiling begins to come down, slowly and jerkily, and soon Hatherley is unable to stand. This part of the tale reminded me of the gradually increasing horror of Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum.” Just in the nick of time, a panel opens and one of the gang, a beautiful woman, pulls Hatherley out and takes him to an outside room. They are in an upper story, but she tells him to jump into the garden. Meanwhile the other German is coming at him with a cleaver. The horror fiction rhythm—danger withdrawn suddenly and then as suddenly renewed—is also reminiscent of Poe. As he hangs from the sill ready to drop into the garden, Hatherley feels the cleaver come down. Unhurt from the fall, he finds his thumb has been cut off. When he recovers himself, he is close to the village’s train station, and he escapes to London. He has his wound dressed by Watson, who takes him to Holmes. When they return to the village with the police, the house where Hatherley was taken is on fire and the occupants have fled. In “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb,” to give it its full title, Watson offers no apology for Holmes’s small part in it or the sensationalism, but rather seems to relish a tale “so strange in its inception and so dramatic in its details.” The story is a precursor to stories by H. C. McNeile, John Buchan, and others, where a ruthless and often foreign gang holds an innocent Englishman prisoner in a lonely country house. Doyle repeats something like it in “The Greek Interpreter” in the next group of stories.

In the abstract, there are few story lines in the Adventures. Stepfather retains stepdaughter’s money by preventing her marriage (two stories); marriage of young hotshot is threatened or aborted by a previous liaison (two stories: king—his liaison and noble bachelor—hers); jewels stolen, son or workman falsely accused, jewels restored and thief allowed to go unpunished (two stories); red-haired person hired to be present or absent so that nefarious activity can go forward (two stories); the long arm of the past strikes from America or Australia (three stories). In this company the class parable of “The Man with the Twisted Lip” and the thriller of “The Engineer’s Thumb” stand out for their uniqueness. Clearly when The Strand Magazine editor Greenough Smith’s praises Doyle’s “ingenuity of plot,” he has in mind the ingenuity with which a plot is treated rather than its absolute originality.

Continue reading, get your copy here… The Golden Era of Sherlock Holmes