“The blues had a baby and they called it rock ‘n’ roll,” said the great Muddy Waters.

But what was the firstborn? What was the first rock ‘n’ roll record?

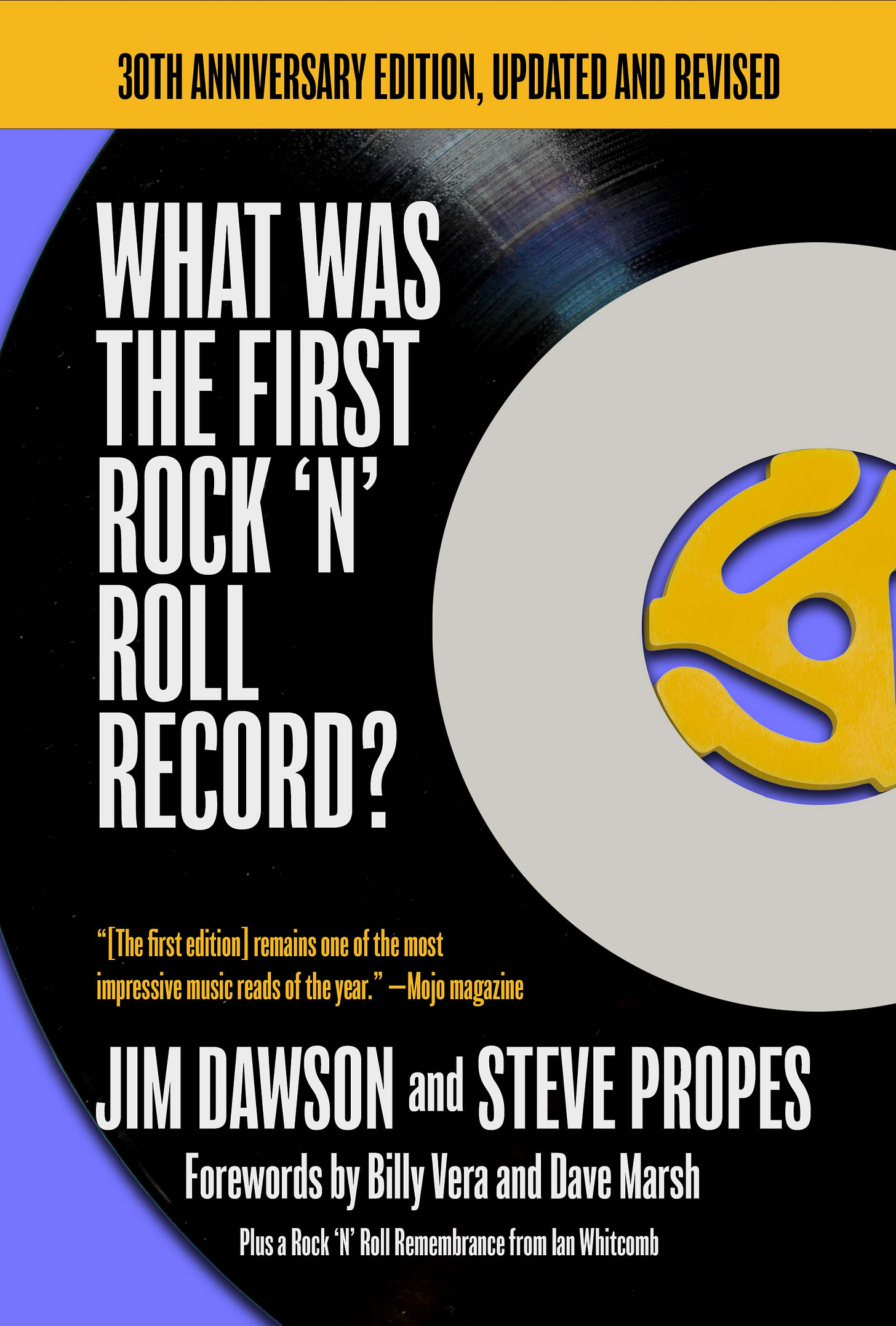

Using this question as their starting point, writer Jim Dawson and DJ Steve Propes nominate 50 recordings for that honor. Beginning with a 1944 Jazz at the Philharmonic recording of “Blues,” and ending with Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel,” What Was the First Rock ‘n’ Roll Record? Profiles some of the most important and influential recordings in rock’s history.

For each nominee, Dawson and Propes provide chart positions, labels, recording information, and an explanation as to why it might qualify as the first. Lesser known milestones like “Open the Door, Richard” and “Rocket 88” appear here alongside acknowledged classics like “Shake, Rattle, and Roll” and “Rock Around the Clock,” and many forgotten artists are restored to their rightful place in rock’s pantheon. The result is a provocative and entertaining guide to the earliest days of rock ‘n’ roll.

This 30th anniversary updated and revised edition brings to light new and surprising details about the songs, albums, and artists that are vying for the honor of being the first rock ‘n’ roll record.

1 BLUES, PART 2

by Jazz at the Philharmonic, featuring Illinois Jacquet

Chart position: Did not chart

Category: Jazz/R&B

Writer: Entaoin

Label/number: Stinson 624

Flipside: “Blues, Part 1”

When & where recorded: July 2, 1944, in Los Angeles

When released: Late 1944

Why important: It was one of the first “live” commercial recordings; Illinois Jacquet’s solo performance launched a school of highly emotional “honking and squealing” saxophone playing that became a staple of R&B and early rock ‘n’ roll

Influenced by: “Seven Come Eleven” by the Benny Goodman Sextet (1939), and Jacquet’s own earlier solo on Lionel Hampton’s “Flying Home” (#23 Pop, 1943)

Influenced: Every R&B saxophonist from Wild Bill Moore and Big Jay McNeely to King Curtis and the Comets’ Joey D’Ambrosio and Rudy Pompilli

Important remakes: “Jet Propulsion” by Illinois Jacquet (1947) and “Rockin’ at the Philharmonic” by Chuck Berry (1958)

The story behind the record: Los Angeles-native Norman Granz was a twenty-six-year-old film editor at MGM Studios who, in his spare time, ran all-star jazz jam sessions at clubs around town. Coming from a Ukrainian-Jewish family, he was sensitive enough to ethnic and racial discrimination that he insisted on whites and blacks being allowed to play together on stage at his shows and sit together in the audience. In 1944 he was holding a weekly get-together at the new 331 Club on Eighth Street, just east of Normandie. “I worked there every Monday for twenty-one Mondays,” said tenor saxophonist Jack McVea. “Nat ‘King’ Cole had the regular group there, but then he got a hit record going [‘Straighten Up and Fly Right’], so [clarinetist] Barney Bigard called me up and asked me to take over.” Whoever was in town would show up, and patrons could expect to see some of the top names in jazz.

The sessions got so popular that one day someone kidded Granz, “Hey, why don’t you put this in the Philharmonic? They’re not doin’ nothing.”

The impressive beaux-arts Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium, downtown at 427 West Fifth Street overlooking Pershing Square, was the staid home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and was generally filled with soaring arias and symphonies. Ragtag jazz seemed as out of place there as Pagliacci wearing a porkpie hat. But the thirty-eight-year-old edifice could hold 2,300 people, and nobody was using it most Sunday afternoons, so Granz arranged a major jazz concert there. As usual, one of his stipulations with the management was that blacks would not be barred from attending the show or shunted into the balcony. This provided an ironic touch, since the theater—once known as Clune’s Auditorium—was where D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a paean to the Ku Klux Klan, had its world premiere in 1915 and packed the house twice a day for months afterward. Granz also agreed to donate most of the concert’s profits to a defense fund to help several Mexican-American youths wrongly convicted for murder during the infamous “Zoot Suit” riots in June of the previous year, when a mob of drunken servicemen rampaged through the barrio near downtown, beating up pachucos and tearing off their baggy, draped suits.

When Granz set up his first Jazz at the Philharmonic concert on Sunday afternoon, July 2, 1944, he packed the joint. “That first session,” Jack McVea recalled, “people was trying to get in the place after it was closed.”

Granz himself hadn’t thought of recording the event, but a friend, Jimmy Lyons, who worked for the Armed Forces Radio Service, “asked my permission to record [the artists] on those old sixteen-inch disks,” Granz said.

The Armed Forces Radio Service generally recorded jazz and swing concerts in Los Angeles as part of its Jubilee series of broadcasts for black military men, who at that time served in segregated units. These concerts were edited down onto twelve- or sixteen-inch, 78-rpm transcription disks and sent to short-wave radio stations around the world. Jazz at the Philharmonic fit perfectly into the Jubilee program.

For his rhythm section, Granz recruited drummer Leonidas “Lee” Young (saxophonist Lester Young’s twenty-seven-year-old kid brother, who led the house band at the Club Alabam on Central Avenue) and the Nat Cole Trio: pianist Nat Cole, guitarist Oscar Moore, and bassist Johnny Miller. The trio’s presence demonstrated their high regard for Granz, because by now they were major recording stars with two Harlem Hit Parade hits behind them and a current record, “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” sitting at the top of the chart (for a total of ten weeks) and winging over into pop terrain.

Cole had settled in Los Angeles a couple of years earlier after being stranded by the collapse of the road troupe of the Broadway revue Shuffle Along. Born Nathaniel Adams Coles in Montgomery, Alabama, on March 17, 1917, he grew up in Chicago. Though his biography implies that he accidentally became a singer after he was already known as a first-rate jazz pianist, in fact he sang on his first recordings in 1938, issued under the name the King Cole Swingsters. Now recording for Capitol Records, only in the past year had he established his velvety voice as commercial gold. In order to play at the JATP he used a dummy name, Slim Nadine, and limited himself to the ivories. Nadine, incidentally, was his wife’s name.

Bassist Johnny Miller, a native of nearby Pasadena who had recently joined Cole’s trio, showed up for the gig, but Oscar Moore was reportedly shacked up with a hot babe and a bottle, so Cole asked his friend Les Paul to sub him on guitar. Since Paul was in the army at the time and not allowed to record as a civilian musician, he also, like Cole, assumed a phony name for the day: Paul Leslie.

Rounding out the crew was the horn section: Illinois Jacquet and Jack McVea on tenor saxes, and a twenty-year-old trombone player from Benny Carter’s band named J.J. Johnson.

The combo started the afternoon with Lester Young’s “Lester Leaps In,” then moved into another instrumental, a head arrangement that McVea called “just a traditional blues, with standard blues changes we could all play,” although the beginning riff bears a close resemblance to bandleader Benny Moten’s 1933 “Moten Swing” and the Benny Goodman Sextet’s 1939 “Seven Come Eleven.” After Nat Cole kicks off the number, McVea takes over and establishes the melody with a chorus of rich tenor sax. J.J. Johnson follows with an extended trombone solo. Then, as the tune heats up, Illinois Jacquet steps forward and launches into two-and-a-half-minutes of rabble-rousing. He slips way down into his horn and brings up a throaty growl that rises from the bell like a tornado. He shrieks, squeals, pinches off the ends of his phrases somewhere in the stratosphere. Each new assault on the melody drives the crowd into a frenzy.

For a general audience, this was something new, a mixture of stage antics and musical pyrotechnics that, in only a few manic choruses, blew open the boundaries of jazz and rhythm and blues. On that July day at the Philharmonic, Jacquet introduced the phenomenon of the honking saxophonist [see #9, “We’re Gonna Rock”], and black music—hell, American music—would never be the same again!

Jean-Baptiste Illinois Jacquet was born in Broussard, Louisiana, on October 31, 1922, and raised in Houston, Texas. He was a big, handsome, green-eyed kid who blew a big-voiced tenor. Moving to the West Coast in 1941, he joined Lionel Hampton’s band and wrote his indelible signature on the coming decade with his impassioned solo on Hampton’s “Flying Home,” one of the first identifiably rhythm and blues hits. Jacquet was playing with Cab Calloway’s orchestra when he got the nod to play at the Philharmonic.

The show was a ringing success. Granz scheduled another concert at the auditorium the following month and invited back some of the same musicians, including McVea and Jacquet. During that jam, Jacquet knocked out the audience with an overheated rendition of “How High the Moon” that would later change the fortunes of JATP. But because the fans at the two events were unruly (McVea recalled that several jivers “ripped up the seats”) and some people resented the integrated seating policy, the Philharmonic management told Granz he wouldn’t be welcomed back. He moved the show to the larger Shrine Auditorium not far away, on Jefferson Boulevard. Though Granz never returned to the Philharmonic Auditorium, he kept the name Jazz at the Philharmonic for its commercial ring.

After the Armed Forces Radio Service aired the July concert for servicemen around the world, Granz carried his JATP masters, along with a dozen or more other recordings, to New York City on a business trip. When Columbia Records turned him down, he contacted Moses Asch, a Polish immigrant who had been recording blues, gospel, and folk music since the late 1930s. Asch’s biggest artists were Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie. At first Granz tried to sell him a dozen sides by a jazz singer named Ella Logan, but Asch wasn’t interested. However, he did want to hear some of those other disks Granz was toting. The minute the needle touched down on a live recording of Jacquet playing a bopped-up version of “How High the Moon,” Asch was hooked. He agreed to release an album with selections from the first two Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts.

An album in the mid-‘40s was indeed an album: several sleeved records within a cardboard-covered book. Normally these albums were made up of ten-inch 78-rpm records—the normal size—but Granz and Asch needed a different format. The musicians had played without any thought of limiting their solos to fit comfortably on the side of a ten-inch platter, which held less than three and a half minutes of music. This required that Granz carefully edit the numbers, fading out at the end of a chorus so that the performance could fit on one side of a record, and then fading back in with a few seconds of overlap on another side. To get as much time per side as possible, Asch pressed the recordings onto twelve-inch 78s, which could hold over five minutes of music. (The twelve-inch format would later accommodate the microgroove 33-1/3 LP, which was an album in name only.)

Along with “How High the Moon,” Asch and Granz decided to release the improvised blues number. They named it simply “Blues.” At ten and a half minutes long, it had to be split into two sides. The Jack McVea and J.J. Johnson solos dominated the first side, “Part 1.” Jacquet’s blistering solo and a humorous chase between Nat Cole and Les Paul were the centerpieces of “Part 2.” The so-called composer, “Entaoin,” was a dummy name. Nobody copyrighted “Blues” at the time and no record of Entaoin exists.

Because of a wartime rationing of shellac—the Indian gum required to make the “wax” for 78s—Asch was faced with an inventory problem. He solved it by linking up with Hubert Harris, president of Stinson Records, who had specialized in releasing Russian music in the U.S. until World War II cut off his sources. Asch had music but no shellac; Harris had shellac and no music.

Their release of live material was a commercial risk. Up until then, transcriptions of public performances were used for radio programs, mostly to allow shows airing on the East Coast to be replayed in the western time zones hours later. Because of the still primitive technology, no one had thought to commercially release anything that hadn’t been recorded in the controlled environs of a studio. But jazz, with its flights of improvisation, often sounded better live. The JATP concert recordings became the first “live” albums.

Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic turned into a perennial success, but Asch soon severed their partnership because he felt the producer spent too much money on recording his artists. Granz leased his JATP material to other labels, including Mercury, but eventually he formed his own record companies, Clef, Verve, and later Pablo. The concerts spawned one hit, “Mordido,” featuring Illinois Jacquet, in 1949. Ten years later Granz took the JATP overseas and continued to hold concerts in Europe and Japan until the 1980s. He died of cancer on November 22, 2001, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Jacquet joined Count Basie’s Orchestra shortly after the 1944 concerts, gradually abandoned his pyrotechnics, and became a respectable jazz musician—but not before he remade “Blues” under the name “Jet Propulsion” for RCA Victor in 1947. Illinois Jacquet died in New York of a heart attack on July 22, 2004.

With the international success of “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons” in 1946, Nat “King” Cole evolved into a major pop star and influenced a generation of smooth balladeers, including Frankie Laine, Charles Brown, Ray Charles, Johnny Ace, and Jesse Belvin, to name a few. Cole died of lung cancer on February 15, 1965. Les Paul teamed successfully with wife Mary Ford, helped pioneer the technology of multi-track recording [see #23, “How High the Moon”], and defined the rock ‘n’ roll guitar solo. J.J. Johnson became an internationally celebrated bebop trombonist and recorded with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis; Johnson died in Indianapolis in 2001. Drummer Lee Young challenged the Hollywood power structure and became one of the first black musicians to sit in with film studio, radio, and later television orchestras. He died in 2008. And Jack McVea co-wrote and recorded one of the biggest hit records of 1947 [see #6, “Open the Door, Richard”]. The Philharmonic Auditorium was torn down in 1985 to clear the way for a parking lot.

When Chuck Berry recorded an instrumental in 1958 called “Rockin’ at the Philharmonic,” he credited it to tunesmith Chuck Berry. In fact, the number was “Blues.”

Purchase the book here: What Was the First Rock N Roll Record?