In the fifth installment of Beyond Baker Street, author David Foster takes us deep into the smoky reels of early Hollywood, tracing the sinister shadow of Doctor Fu Manchu. From Warner Oland’s yellowface performances to Anna May Wong’s star-making (and underpaid) turn in Daughter of the Dragon, Foster explores the complex and often problematic cinematic legacy of the so-called Devil Doctor.

This isn’t just a look at vintage thrillers—it’s a lens on how race, power, and pulp storytelling collided on the silver screen.

Fu Manchu in Film: The Early Years

G’day friends. Welcome to the second installment of this series on the nefarious Doctor Fu Manchu. This time around, I’m turning my attention to a few of the early cinematic adaptations of the Devil Doctor.

Sadly, Hollywood’s penchant for casting white actors as Asian characters and having them don yellow-face was a common occurrence. If it wasn’t so racist, it would almost be laughable. Consider this, German actor Peter Lorre played Mr. Moto eight times, English actor Boris Karloff played Mr. Wong five times, and Swedish actor Warner Oland played Fu Manchu on four occasions. Oland would become typecast playing Asian characters. Along with Fu Manchu, he would later go on to play Charlie Chan in at least 16 films, and several shorts. Things hadn’t changed much even in the 1960s, when Christopher Lee played Fu Manchu with prosthetic eye pieces to make him look Asian.

However, for this series of Fu Manchu film reviews we’ll put the casual racism and crude ethnic stereotypes to the side. Just take it as a given that the films under discussion are not politically correct, and viewer discretion is advised.

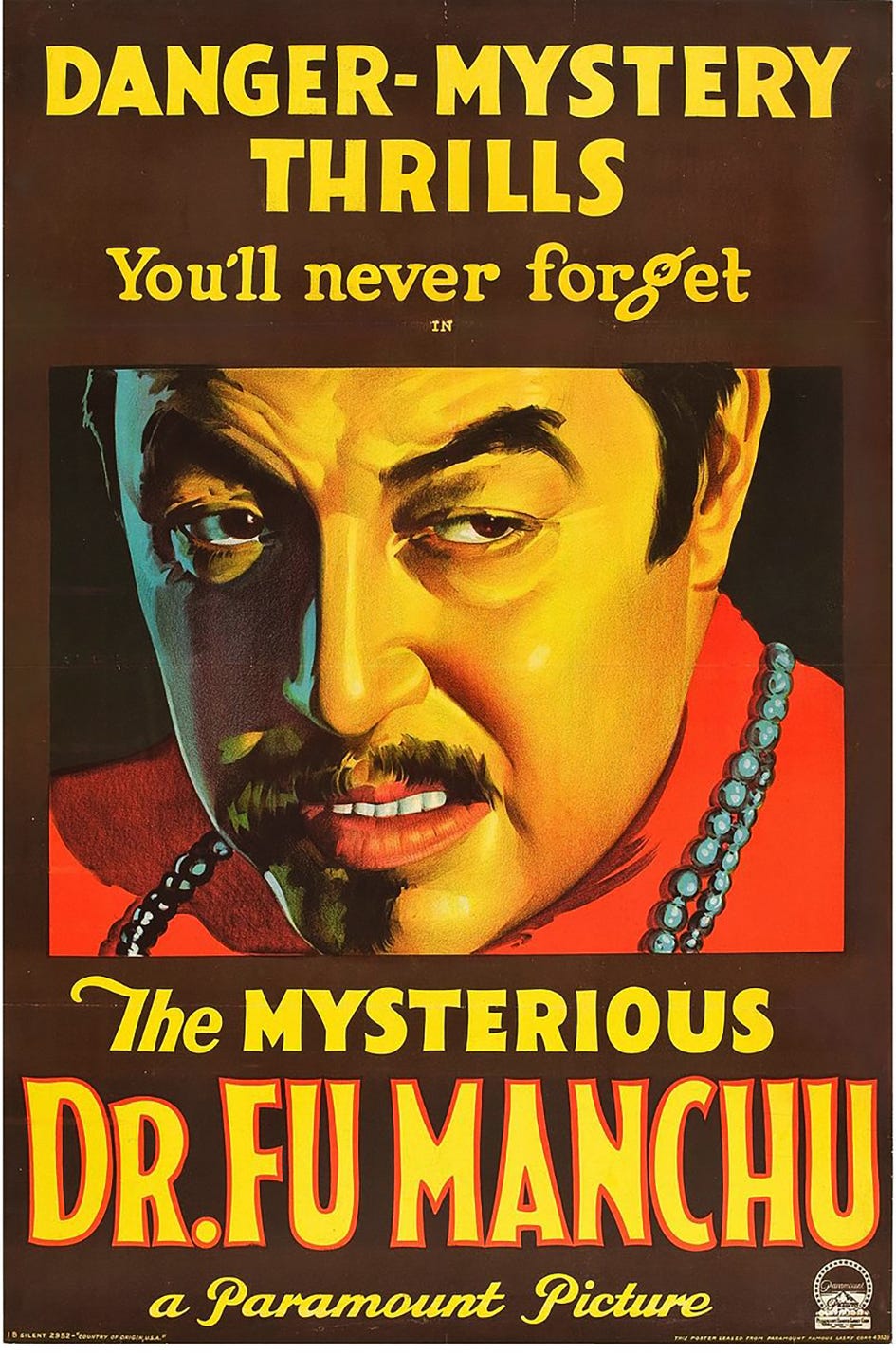

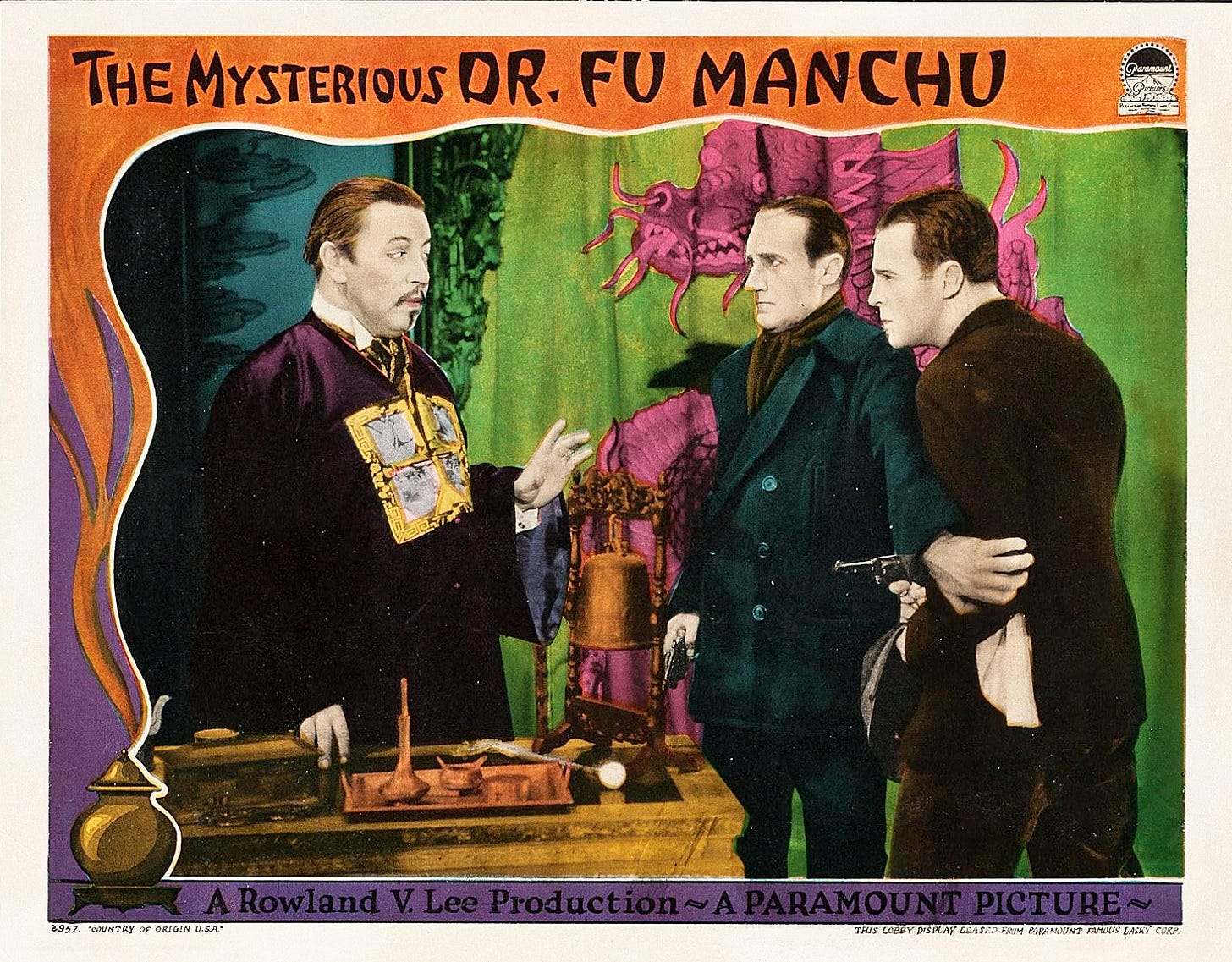

The Mysterious Fu Manchu (1929)—AKA: The Red Dragon—stars Warner Oland in the title role, O.P. Heggie as Inspector Nayland Smith, and Neil Hamilton as Dr. Petrie. Oland is probably best known for his role as Charlie Chan, but The Mysterious Fu Manchu is the film that turned him into a star—albeit typecast as foreign gentlemen, more often than not, an Asian gentleman.

The critics of the day were impressed with The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu. The following review appeared in the Cootamundra Herald on Tuesday 17 December 1929.

“DR. FU MANCHU”

Every audience will love to join the great detective Nayland Smith in his mad adventurous chase of that wily oriental character, “The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu,” taken from the pages of Sax Rohmer’s world-famous book and made to live on the screen at the Arcadia Theatre on Wednesday.

Gripping, awful mystery—eerie footsteps in the dead of night—an unseen hand spreading terror and destruction—a beautiful girl hypnotised to work the will of a cruel maniac—and love dominating, controlling, triumphing, in the mystic maze of [a] revengeful career.

‘The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu’ is one of the greatest mystery stories ever written; and it is one of the greatest moving pictures ever made. In swift action, the strange, crafty villain, who thrilled millions in Sax Rohmer’s books, comes to life, spreads out before us on the screen, inspires us with a nameless terror, spurs us on to his capture, and leaves us with a thankful feeling of relief when captured at last, he clears the way for true love.

Warner Oland in the title role is great. The master villain of the screen has been doing oriental roles for years, but never have his performances approached the perfection of this one. Jean Arthur and Neil Hamilton are irresistible as a pair of young lovers. Everybody loves with them.

Warner Oland would play Fu Manchu on three more occasions: The Return of Dr. Fu Manchu (1930), Daughter of the Dragon (1931) alongside Anna May Wong, and a brief cameo in the Murder Will Out portion of Paramount on Parade (1930), which also featured Clive Brook as Sherlock Holmes.

Despite the titles stating Daughter of the Dragon (1931) is based on Sax Rohmer’s Daughter of Fu Manchu, the stories share no connection. Paramount didn’t own the rights to Rohmer’s story. The film is about a vendetta the Fu Manchu family have against the Petrie family—Nayland Smith does not appear in the film.

The film begins with celebrated Oriental dancer Ling Moy (Anna May Wong) waiting to hear from her father. Her father disappeared from her life when she was very young. She doesn’t know who he is.

Meanwhile, after lying in wait for 20 years, Fu Manchu (Warner Oland) strikes at the Petrie family, poisoning Sir John Petrie, and attempting to kill his son, Ronald (Bramwell Fletcher). In the confrontation, Fu Manchu is shot but he manages to escape through a secret tunnel.

Ling Moy returns home after a performance and finds her father waiting. He has a gunshot wound and is dying. On his deathbed, he confesses he’s arch-criminal Fu Manchu, and despite his 20-year absence from her life, asks her to swear to deliver the soul of Ronald Petrie to him in the afterlife. Ling Moy swears she will do her father’s bidding; however, the task isn’t easy when she falls in love with Ronald Petrie

It’s been suggested, Anna May Wong’s $6,000 salary, half what Oland was paid, even though Oland had less screen time, is an example of Hollywood’s racism.

On Anna May Wong’s starring role in the Daughter of the Dragon, on Friday 15 January 1932, Perth’s The Daily News reported:

ANNA MAY WONG

Starring Role

The end of a self-imposed trial period in motion pictures has just arrived for Anna May Wong, with the portrayal of the greatest role in her career. She heads the cast of ‘Daughter of the Dragon,’ with Warner Oland and Sessue Hayakawa.

Ten years ago, at the age of 12, Miss Wong sought a screen career. She told herself that she would devote a decade of her life to the struggle. If at the end of that time she had not succeeded she would retire from the pictures.

A talented singer, dancer, linguist and convincing actress, Miss Wong has discovered her forte in talking pictures. Her success in ‘Daughter of the Dragon’ has ensured her an equally important role in Marlene Dietrich’s forthcoming ‘Shanghai Express.’ She will not leave the screen now.

While the reviews were favourable, some of the press at the time seemed more interested in what Anna May Wong was wearing, rather than the film. The following snippet appeared in The Cumberland Argus on Monday 11 April 1932.

ANNA MAY WONG

Adhering to the trend of Eastern invishness, Anna May Wong, Chinese player, appearing in Paramount’s “Daughter of the Dragon,” which opens at the Cinema Theatre Saturday next, and continues for one week, selected a wardrobe for this production that combined the allure of the orient with the chic of the occident.

You can read my thoughts on when Sherlock Holmes met Fu Manchu in Cay Van Ash’s Ten Years Beyond Baker Street in 52 Weeks, 52 Sherlock Holmes Novels— a multi-personal look at fifty-two of the best Sherlockian pastiches—edited and collated by Paul Bishop.

Beyond Baker Street

I’ve always been fascinated by the shadow cast by Sherlock Holmes—a figure so iconic that his influence seeps into unexpected corners of pop culture. Beyond Baker Street is where I chase those echoes. Whether it’s a villain who once faced Holmes or a story that feels like it should’ve, this series lets me explore the strange tributaries that flow from the great detective’s world.

If you’ve enjoyed this piece, you’ll find even more to explore in my book Baker Street: The Curious Case Files of Sherlock Holmes—a deep dive into 100+ years of Sherlock Holmes in print, film, television, and beyond. From Conan Doyle’s original stories to pastiches, parodies, and pop culture echoes, it’s a must-read for Holmes fans and curious minds alike.

Yours in the Spirit of Adventure

David Foster is an Australian best-selling author who writes under the pen names James Hopwood, A.W. Hart, and Jack Tunney. Under the latter, he has contributed three titles to the popular Fight Card series. His short fiction has been published in over 50 publications worldwide, including by Clan Destine Press, Wolfpack Publishing, and Pro Se Productions, to name but a few. In 2015, he contributed to the multi-award-winning anthology Legends of New Pulp Fiction, published by Airship 27 Publishing.

Foster’s non-fiction work appeared in the award-winning Crime Factory Magazine, as well as contributing numerous articles exploring pulp fiction in popular culture to Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (2017, PM Press) and Sticking It to The Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 (2019, PM Press). He has also contributed articles on the ANZAC war experience to Remembrance (2024, Union Street 21).

Foster lives in the old Pentridge Prison Complex, behind high grey stone walls, in inner-suburban Melbourne, Australia.