Think of Sherlock Holmes and you likely imagine a pipe, a magnifying glass, and razor-sharp deduction.

But Holmes wasn’t just a brain—he was also a brawler.

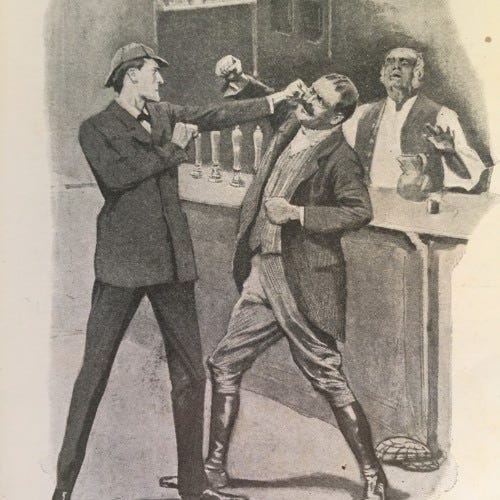

In this fascinating essay, Paul Bishop explores a lesser-known element of Conan Doyle’s outstanding detective: his boxing prowess. Holmes’ fights—whether in print or on screen—reveal a man as disciplined in the ring as he is at the crime scene.

🧠 Brain Meets Brawn

"You are Sherlock Holmes, the amateur who fought three rounds with me at Alison’s rooms in 1877?"

— The Sign of Four

From Victorian bare-knuckle bouts to Guy Ritchie’s kinetic film scenes, Holmes’ physicality is not a footnote—it’s foundational. Bishop explores the historical and cultural lens behind Holmes’ skills and how modern authors and actors bring that dimension to life.

Now, enjoy Paul Bishop’s full essay exploring the physical side of Sherlock Holmes—and how boxing became one of the detective’s most underrated tools.

Sherlock Holmes, the legendary detective created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is celebrated for his brilliant intellect, acute observational skills, and logical reasoning. Yet, among the many talents that make Holmes a remarkable figure in detective fiction is his proficiency in the noble art of boxing. While not often the centerpiece of Conan Doyle’s stories, Holmes’ boxing prowess forms a crucial component of his character, representing both his physical competence and his embodiment of Victorian ideals of masculinity.

Holmes’ connection to boxing is mentioned explicitly in several stories. In The Sign of Four, for instance, Holmes and Dr. Watson visit a professional boxer, McMurdo, to inquire about the villain Jonathan Small. During the conversation, McMurdo recognizes Holmes as a former amateur boxing champion, exclaiming, I’m not mistaken? You are Sherlock Holmes, the amateur who fought three rounds with me at Alison’s rooms in 1877? This brief but telling moment affirms Holmes’ history in the ring and highlights the respect he earned even among professionals.

Boxing in the Victorian era was undergoing a transformation, emerging from its brutal bare-knuckle origins into a more regulated sport with rules and cultural respectability. Holmes’ involvement in boxing aligns him with the image of the gentleman athlete—someone who cultivated both mind and body, discipline and physical readiness. Unlike many of his era who would regard physical violence as base or uncivilized, Holmes approaches it as a necessary and controlled form of action, an extension of his detective work when intellect alone cannot suffice.

Holmes uses his boxing skill not only to defend himself but also to assert control in dangerous situations. In The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist, Holmes famously knocks down the villain Woodley with a single punch, showing that when deduction ends, swift and decisive action may begin. His physical ability complements his mental acuity, portraying him as a complete man—brain and brawn in balance. His mastery of other martial skills, like baritsu (a Japanese-inflected form of martial arts mentioned in The Adventure of the Empty House), reinforces this disciplined, strategic approach to violence.

This dimension of Holmes’ character is explored and celebrated in Andrew Salmon’s Fight Card: Sherlock Holmes books—specifically Work Capitol and Blood to the Bone. These pastiche novels blend the grit of pulp boxing fiction with the deductive elegance of Sherlock Holmes, offering readers thrilling stories where boxing is not just an element of color, but central to the plot and character dynamics. Salmon understands Holmes not only as a cerebral detective but as a man of action. He crafts scenes in which Holmes’ boxing skills are crucial to the resolution of the mystery, giving weight to what Conan Doyle only hinted at.

Salmon’s writing stays faithful to the tone and voice of the Holmes canon while injecting a hard-hitting, kinetic energy drawn from the world of pugilism. The boxing matches are vividly described, and the ring becomes a microcosm of Holmes’ broader world—a place where strategy, observation, and willpower decide the outcome as much as brute strength. These novels also give Watson a more physical presence, emphasizing his military background and reliability in a scrap, which enhances the partnership in believable and exciting ways.

Robert Downey Jr.’s portrayal of Sherlock Holmes in Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes films (2009, 2011) reimagines the legendary detective as both brilliant mind and formidable physical force—a depiction that brings Holmes’ canonical boxing skills to the forefront in a stylized, kinetic way.

Downey’s Holmes is scrappy, unkempt, and highly cerebral, but what sets this version apart is how directly his intellect informs his combat. In several memorable fight scenes, Holmes mentally rehearses each move before executing it with clinical precision—a cinematic device that underscores his analytical prowess even in violence. This approach aligns well with Conan Doyle’s subtle references to Holmes as a capable boxer and practitioner of baritsu, but cranks up the energy to suit modern action audiences.

While purists may find the emphasis on hand-to-hand combat a departure from the more restrained Holmes of the page, Downey’s performance, under Ritchie’s dynamic direction, convincingly bridges brain and brawn. He doesn’t fight recklessly; rather, every blow is calculated, making his fighting style a natural extension of his detective methodology.

Ultimately, Downey’s Holmes may be a more action-oriented interpretation, but it stays true to an often-overlooked part of the character—Holmes as a fighting man, capable not just of deducing danger, but of confronting it head-on.

Jeremy Brett’s portrayal of Sherlock Holmes in the Granada Television series (1984–1994) is widely regarded as the most faithful to Conan Doyle’s original vision—elegant, eccentric, and intellectually fierce. While Brett's Holmes is not often seen engaging in physical combat, his portrayal subtly acknowledges Holmes’ boxing background without turning it into spectacle.

In episodes such as "The Solitary Cyclist" and "The Final Problem," Brett’s Holmes shows flashes of physical agility and readiness, suggesting a man who could fight effectively if needed, even if he prefers to rely on intellect. His movements are deliberate and poised, and his lean frame carries the wiry energy of a trained fighter. The series hints at Holmes’ past as an amateur boxer (notably in the aforementioned Cyclist episode, where he decks the villain with authority), but always within the genteel bounds of Victorian restraint.

Brett’s Holmes embodies the idea that boxing, for the detective, is not for sport or bravado but a tool—refined, controlled, and used only when deduction alone will not suffice. His performance gives viewers a Holmes who is more likely to outthink than outfight his opponents, but who nonetheless carries the quiet confidence of a man who can do both.

In sum, boxing is not merely an incidental hobby for Sherlock Holmes; it is a significant facet of his character reflecting the values of his time and the depth of Conan Doyle’s creation. Holmes is not just a cerebral sleuth but a man prepared to act physically when the situation demands. Andrew Salmon’s Fight Card entries, Robert Downey Jr’s interpretation of Holmes on film, and Jeremy Brett’s portrayal of Holmes on television effectively spotlight and expand this often-overlooked aspect of the great detective, providing a rewarding experience for fans who appreciate the fusion of mystery and action. Holmes in the ring is still Holmes—precise, calculating, and formidable.

Paul Bishop is the editor of 52 Weeks 52 Sherlock Holmes Novels—a multi-personal look at fifty-two of the best Sherlockian pastiches—available from Genius 52 Weeks - 52 Sherlock Holmes Novels